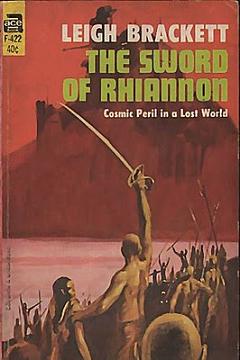

The Sword of Rhiannon

Leigh Brackett

141 pages

published in 1953

You may think you don’t know Leigh Brackett or read any of her stories, but you’re wrong. If you think The Empire Strikes Back is the best of the real Star Wars movies, you have her to thank for it, as she wrote the original screenplay, just before she died. This is no fluke either, as her screen writing career is almost as old as her science fiction career. She started off on The Big Sleep together with William Faulkner and has worked on other well known movies like Rio Bravo and The Long Goodbye. And with her long She knew her way around a film script; combine that with her long experience writing science fantasy for pulp magazines like Planet Stories and you know why Empire is so much better than any of the other Star Wars movies.

If you liked Empire than the good news is that Leigh Brackett is even better when working on her own stories. Though she wrote other science fiction, she’s best known for writing planetary romances (or science fantasy) in the tradition of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Her best stories are set on the Mars of Burroughs and dozens of pulp imitators, a dying world turned into a worldwide desert as its seas dried up, with a highly evolved but degenerated civilisation clinging to life through an elaborate system of canals, now turned into a new version of the Western frontier as Terran adventurers and never do wells come to try their luck. Brackett’s Mars is more than just a pulp adventure setting though. Her best stories leave you with a sense of melancholy and loss, perhaps nowhere more so than in The Sword of Rhiannon, “a hymn to the lost past of a Mars that never was” as Nicola Griffith put it in her introduction to a recent reissue.