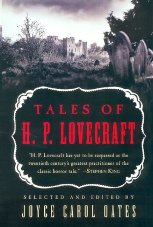

Tales of H. P. Lovecraft

H. P. Lovecraft

Joyce Carol Oates, editor

328 pages

published in 1997

It’s almost embarassing to say this, but apart from the occasional short story in an anthology here or there, this is the first I’ve read of H. P. Lovecraft. Just as well then that this is an excellent introduction to Lovecraft, featuring many of his most famous works. The stories have been selected by Joyce Carol Oates, an not entirely unknown writer herself. What I like about Tales of H. P. Lovecraft is that she has managed to create a well balanced collection without any weak stories. It starts off slow, with several more conventional horror stories, the stories increasing both in length and sophistication, slowly immersing you in Lovecraft’s world.

Despite having only sampled Lovecraft in the past, I pretty much knew what to expect, since his influence is so pervasive in science fiction and fantasy literature. Even if you’ve never read any of his stories, you’ll probably have encountered some pastiche, homage or reference to him in other writers’ work, even discounting those authors like Derleth who imitated him outright.