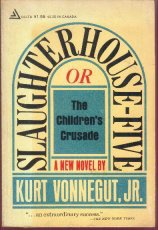

Slaughterhouse-Five

Kurt Vonnegut

215 pages

published in 1969

Back in the days when I read every book in the local library which had that little squiggle on it that meant it was science fiction, I read and reread a hell of a lot of Vonnegut. Books like Breakfast for Champions,God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Slapstick and of course Slaughterhouse-Five. At the time I read them without any consideration of their literary status, but simply because Vonnegut was a science fiction author and I read science fiction, even if much of the Vonnegut novels I read weren’t quite science fiction. I liked them for their cynical black humour and inventive, seemingly slapdash plots.

Rereading Slaughterhouse-Five some twenty years later it’s easy to see why it made such an impression as a work of literature and why it’s so popular with generations of English students. It’s chock full of the sort of symbolism that makes it an easy book to dissect in a student essay. However, that also makes it hard to write about now, almost forty years after its first publication, because so much has been written about it already. I don’t want to write a review that comes over as yet another student paper.