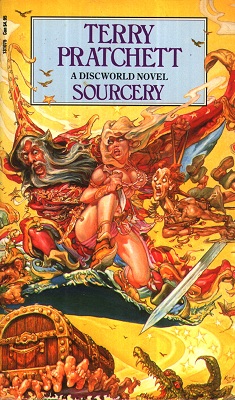

Sourcery

Terry Pratchett

285 pages

published in 1988

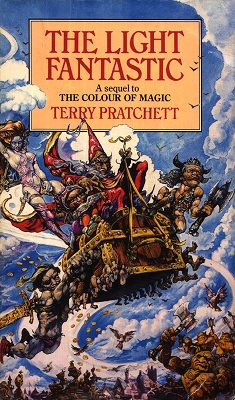

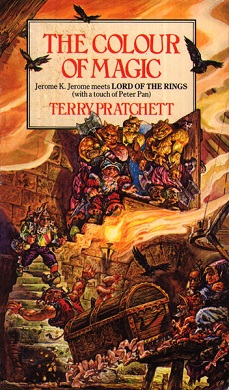

Sourcery is the fifth Discworld novel and the first one after the initial two novels to star Rincewind again. Over time fan opinion has switched to thinking the Rincewind novels are the weakest in the series, but I’ve always liked them myself and I think Sourcery holds up as well as any of the other early novels. It’s the first novel in which there’s a real villain, the first time we get to see what makes a real villain in Pratchett’s eyes.

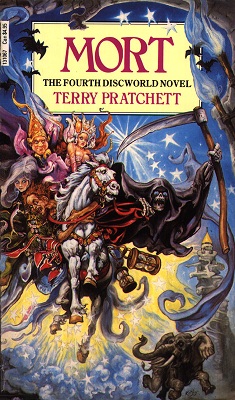

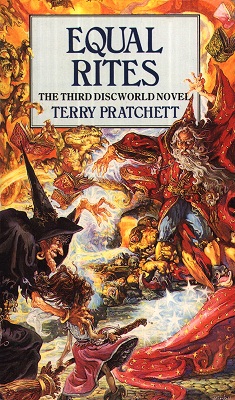

On a surface level there are some similarities to Equal Rites: again there’s a powerful, untrained magic user coming to Ankh Morpork to shake up the Unseen University, but this time he’s not so benign. Coin is not the eight son of an eight son, but the eight son of a wizard. And when a wizard has an eight son, that son doesn’t become a wizard himself, but a sourcerer, a source of magic. The magic he yields is not the tame, nice magic which is the only kind of magic the Discworld has known for ians, but wild magic, the magic from the dawn of times. Not perhaps the kind of magic you’d want a ten year old boy to have, even if his dead father has possessed his wizard staff to give him counsel.

Needless to say, Rincewind finds himself in the middle of events, even though he does his best not to be. His survival instinct, like those of most of the lower lifeforms at the Unseen Univeristy is good enough that he manages to flee the university just before the sourcerer arrives, taking the Luggage as well as the Librarian to the Mended Drum. Unfortunately, that’s where Conina finds him. Conina, unwilling barbarian heroine due to her father, Cohen the Barbarian, but who’d rather be a hairdresser, has stolen the Archchancellor’s Hat at its own request, to keep it out of hands of the Sourcerer. Now Rincewind is the one wizard who can get it to safety.

If there is any safety to be found on the Disc. With the coming of sourcery, the wizards, who had been more or less peacefully been united in the Unseen University and its complex hierarchy, quickly rediscover the old wizard truth that the natural number of wizards is one. They start building towers and magic wars and the Apocralypse are threatening. And only Rincewind and Conina, as well as wannabe barbarian hero Nijgel the Destroyer, son of Harebut the Provision Merchant, stand against it. Oh dear…

What I’ve said before and will say again about Terry Pratchett is that the real strength in his writing is his humanitarian philosophy, his love of sloppy, sentimental, illogical, emotional humanity, that forms the heart of the Discworld series. His worldview infuses the entire series and it’s hear that for the first time it is made clear, though it would only be spelled out later: the worst evil in the world is seeing people not as people, but as things. Here it’s sourcery that shapes the world according to its whims in search of a supposed magic utopia, without taking any notice of the cost in human life or anybody else’s opinions. It doesn’t want to hurt people, it just doesn’t see them.

Opposed are Pratchett’s all too human heroes and villains, petty, dumb, squabbling, cowardly. They do the right thing because they can do no else, they may be thieves or murderers or worse, but they’re never indifferent. Sourcery is the first Discworld novel in which this basic contradiction is made clear and therefore important in the evolution of the series.