Just before the weekend George Tuska died. Tuska was one of those comic book artists (like Don Heck, Herb Trimbe, Vinnie Colleta, even Gene Colan at times) who are only known to several generations of comic book readers as disappointing fill-in artists, ill-served as they were by having to survive in an industry where comics books were made like saugages, the artists as interchangable as workers on an assembly line — who cared if it was good, as long as it was fast. So I only knew Tuska from his (increasingly rare) fill-in work in the eighties and seventies, which wasn’t that good but still offered glimpses of his real capabilities.

Tuska started in comics back in the early forties, at a time when the highest aspiration a cartoonist could have was to have his own newspaper strip. He never managed that, but he did have long stints on two classics, Buck Rogers and Scorchy Smith. He also did a lot of work for the various comics sweatshops that were then operating, including for Will Eisner. During the sixties he was one of Marvel’s second bananas (as compared to legends like Ditko and Kirby, his longest work being on Iron Man, on which he had a ten year run from ’68 to ’78. He also worked on various Bronze Age titles like Ghostrider,

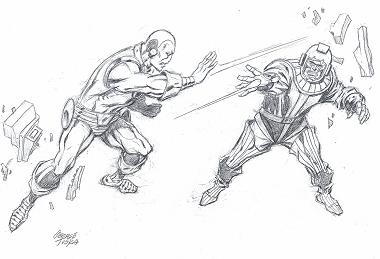

It’s unclear if perhaps Tuska suffered a bit in terms of overall ease making the transition from strips back into comic books, and whether he felt entirely comfortable working under the basic model established by Jack Kirby: his layouts were certainly more imaginative than the standard at the time, and the way in which characters like Luke Cage held a lot of their strength in their shoulders and punched from their legs up through their torsos betrayed his knowledge of strength and fitness. His signature flourish may have been characters in arrested motion, coiled in preparation for violence like so many pulp heroes of an earlier generation, legs splayed in the form of a near-base ready for what might come next. While perhaps slightly diminished in otherworldly power that many comics artists milked from the contrast of stillness and exaggerated movement, Tuska’s heroes almost certainly suffered fewer muscle pulls.

That’s what I remember as well of Tuska, the way his characters stood and moved — you could always tell when Tuska did the art just by that, just like you could with Jack Kirby or Gil Kane. The art above is a good example. Both figures are slightly off centre, Iron Man leaning forward, with Kang leaning backward, one arm outstretched, the other held back for immediate action, both figures balanced on their feet, ready to move if necessary. Though static, there’s a feeling of suppressed movement there, even with the empty background. As Tom Spurgeon says, it shows a knowledge of how real people move, looks far more realistic than a similar Kirby pose, more raw than how Gil Kane would show this scene. That’s what made Tuska’s art always recognisable, no matter how hurried it was.