To the Scheepvaartmuseum with my dad. That’s the Amsterdam, there, a replica of a seventeenth century merchantship that’s moored at the museum. Brilliant, but it was very hot.

To the Scheepvaartmuseum with my dad. That’s the Amsterdam, there, a replica of a seventeenth century merchantship that’s moored at the museum. Brilliant, but it was very hot.

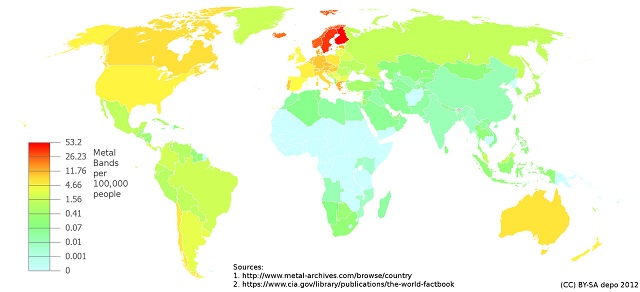

No surprises for the true metal fans here, with Scandinavia having the highest density of metal bands per population. Those long, dark, polar nights are ideal for getting some proper headbanging going.

(Source.)

Tom Spurgeon recommends the comics adaptation of Jack Vance’s short story The Moon Moth

This has to be the oddest stand-alone science fiction comic I’ve read in years. While I can’t tell yet how good it is, it was certainly memorable and I encourage those of you that like such things — and as much as the new science fiction-oriented Image stuff is on everyone’s minds I’m thinking that’s a lot of you — pick this one up and take a look. Jack Vance has an almost Kirby-sized issue with neglect in terms of his influence and the ubiquity of his approach.

Interesting to compare Vance to Kirby, where I can sort of see what Tom means as both were incredibly influential on their own terms and somewhat neglected now, though I do think Vance does not quite have the stature in science fiction that Kirby has in comics, if only because the field is more contested. The true difference between the two is of course that Vance got to keep the copyright and trademarks for all his stories and Kirby could not, which means that we did get a fan driven Vance Integral Edition, but not a Kirby equivalent.

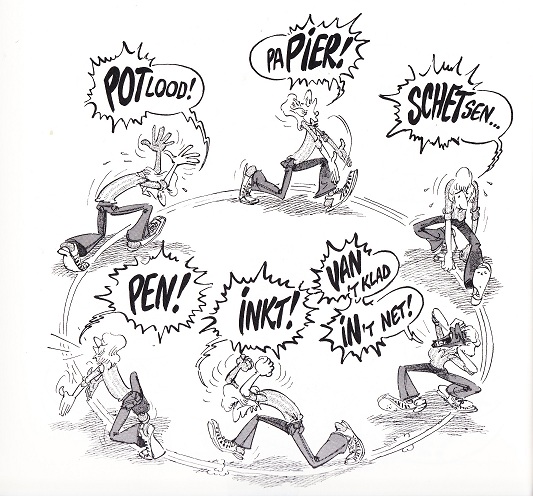

In the eighties Dutch cartoonist Theo van den Boogaard became popular all over Europe with his Sjef van Oekel comic, a classic clear line gag strip subverted by an anarchistic, scatalogical sense of humour. I talked about him last year, when there was an exhibition of his cartoons and architectural drawings in the Amsterdam City Archives. While Sjef van Oekel, despite its anarchistic undertones was a thoroughly commercial comic, van den Boogaard had actually made his reputation in the seventies as part of Holland’s underground scene, with a series of highly personal comics, of which De Ideograaf is one.

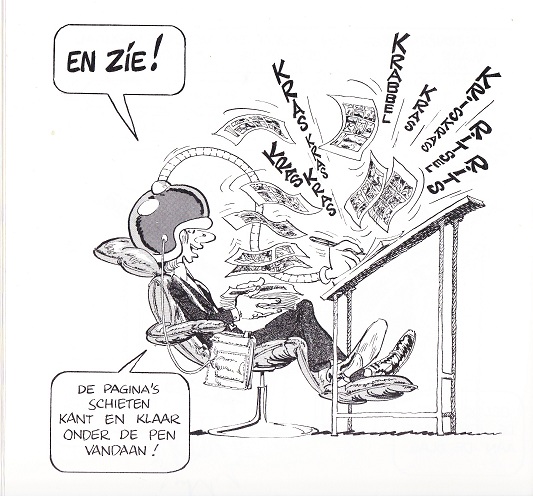

The plot is simple: van den Boogaard, fed up with all the hassle of going from idea to comic, invents a “simple extension of the lie detector” to skip all that tedious writing and penciling and inking and skip directly from the ideas in his head to the finished comic. Van den Boogaard then muses on what this invention would mean for society as a whole, as everybody, not just cartoonists, but other artists as well will be able to realise their ideas perfectly.

What’s great about this is the execution. Van den Boogaard draws in a lighthearted, big footed, big nosed, super exaggerated style, with no panel borders and lots of page filling images as well as several huge two page spreads. I would’ve included such a spread, was it not that my scanner was too small for it; i think the two examples above and below of van den Boogaard’s art give enough of a picture in any case. It’s all incredibly groovy, somewhat reminiscent of e.g. Harvey Kurtzmann or some of the great underground caricaturists (Crumb in his more playful moods, or a Howard Cruse), but also of Franquin.

It’s also very meta; the first quarter of the story has van den Boogaard blowing off steam about the slow production of the very comic it appears in, and throughout he keeps up this knowning wink. Unlike most attempts at being meta it doesn’t come off as forced, as he’s smart enough to trust the reader, doesn’t hit you over the head with it.

To make a long story short, The Ideograaf is one of those rare comics that makes you happy reading it, both for the art and the story as it’s so damn joyfull. A shame it’s out of print when van den Boogaard’s more cynical commercial offerings are still widely available.

One of the more persistent nuisances in British politics is the eagerness in which the government of the day launch populist attacks against the European Court of Human Rights when it rules against them. Whether it’s a Labour or a ConDem government, whenever a ruling goes against them, British sovereignty is endangered by faceless Strasburg Eurocrats and how dare they overrule parliament as the ultimate will of the people. Never mind that Britain has voluntarily chosen to be subjected to the court, or that it doesn’t do anything different from what the UK’s own courts do, i.e. examine government decisions to see if they were made in compliance with the law and if necessary condemn them. That’s an integral part of any true democracy, to have an independent judiciary which can protect the ordinary citizen from governmental abuse of power: parliament to make laws, the government to execute power and the courts to uphold the laws. This is neither new nor controversial, but because this is an European court it’s easier to whip up resentment against it.

Which, to be perfectly clear, is just a special case of the general political resentment against the independent judiciary both Tories and New Labour have had for decades. This was something of a bête noire for Sandra, who as both a trained lawyer and a socialist could get incredibly angry about the way the law was treated, especially by New Labour, busy creating a flood of mostly unenforcable new laws while ignoring existing laws and jurisprudence. She thought that a government so packed full of lawyers should know the limits of the law and what it could and couldn’t do and why it is dangerous for any government to ignore and disrespect it.

In the case of the European Court of Human Rights the damage populist outbursts against it don’t limit themselves to Britain, but far abroad. Though in the UK the ECHR is only mentioned in the context of British court cases, these are only a vanishingly small percentage of its workload; much more important is the role it plays in countries like Russia, countries where the domestic courts are often unable or unwilling to enforce domestic or European legislation both when it’s against the state’s interests. AS Oliver Bullough explains:

The ECtHR’s intray is, as Cameron said, bulging. There are 15,000 pending applications from Turkey, 13,000 from Italy, 12,000 from Romania and 10,000 from Ukraine. But it is Russia that provides the most. Some 40,000 cases from Russia were outstanding by the end of last year, which is more than a quarter of the total.

Russian courts have been reformed since the end of the Soviet Union, but there may as well not have been. Despite efforts to bring in jury trials, transparency and so on, some 98 percent of cases still end in a conviction. In some regions – such as Krasnodar in the south – if the state prosecutors open a case against you and take you to court, you will 100 percent of the time be found guilty.

As it happened, while the British press was fixating on the government’s failure to get Abu Qatada out of the country, these two rulings on Tuesday, April 17 were quietly demonstrating the full range of work that the court does to provide justice for Russian citizens let down by their own court system.

At one extreme, there was a finding in favour of a Chechen woman whose husband had been killed by Russian soldiers. At the other extreme, the court was protecting the rights of those same Russian soldiers against the Russian state. It is hard to imagine how a day’s caseload could be more indicative of the legal nihilism that Russia has sunk into or the importance of Strasbourg in opposing it. In both examples, Russian officials delayed, obfuscated and failed to do the duties they were supposed to do, until the ECtHR slapped them down.

Seen in this context, the concerns British politicans have about the court are revealed for the petty nonsense that they are, but their rhetoric does a lot of harm nonetheless:

The torrent of decisions has not gone un-noticed by top officials. A court decision last summer forcing Russia to give paternity leave to servicemen provoked Alexander Torshin, then acting speaker of the upper house of the Russian parliament, to propose a new law that would guarantee the supremacy of Russian courts over the ECtHR.

“I think that, with its new practices, the Strasbourg Court, departing from the bounds of the European Convention, has moved into the area of the state sovereignty of Russia, and is trying to dictate to the national lawmaker which legal acts it must adopt, which thus violates the principle of the superiority of the Constitution of the Russian Federation in the legal system of our state,” he wrote in an article in the government’s own newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta.

He then listed other countries that have had trouble with the court over the years – Germany, Britain, Switzerland and Austria – using their efforts to find a way to square their own legislation with the court as justification for his own bill.

Although the bill has not got anywhere since it was mooted in July, his article was a clear sign that criticism of the court in western countries where it does little work is amplified in Russia where its work is crucial.

In other words, Cameron and Clegg, like Brown and Blair before them, give cover for authoritarian regimes in Russia and elsewhere in Europe with their petty, party political posturing, potentially allowing one of the few ways in which such governments can be held to account by their own citizens to be neutered. For those of us on the left this should be an incredibly dangerous development, even if we’re often skeptical of the use the courts and the law are put through, as they’re still one of the few ways in which ordinary people can fight back agains the state and without them our own struggles will be that much harder.