The New York Times has an excellent, if slightly triumphalist article up about how the Dutch handle flooding risks and water management in the face of climate change, most of which focuses on the technical nitty gritty, but which also has some insight in the mentality behind them:

“It’s in our genes,” he said. “Water managers were the first rulers of the land. Designing the city to deal with water was the first task of survival here and it remains our defining job. It’s a process, a movement.

“It is not just a bunch of dikes and dams, but a way of life.”

Of course it’s a way of life in a country that has been literally won from the sea which without dykes would be three quarters flooded. It’s no coincidence that the waterschappen — the local water management equivalents of city councils or muncipalities — are our oldest democratic institutions. The Netherlands is shaped by a thousand year struggle of keeping out the sea, winning new land from it and regaining what was lost through storms and flooding. With the most recent disastrous flood still firmly in living memory, it’s no wonder there’s a seriousness to water management and climate change that a country like the United States, perfectly willing to let a major city drown, lacks.

So while our politicians might be just as idiotic and in denial about climate change as anywhere else, there is no debate on how to counteract the consequences of it for our country, at least in this context. However, this hasn’t gone entirely without a hitch. The current water management approach and philosophy took time to evolve, in some ways is diametrically opposed to traditional Dutch values.

The instinctive response to the floodings of 1953 was to immediately start strengthening the dykes, but now systematically, according to the socalled Delta Plan. Instead of just strengthening the existing dykes, the decision was made to redue the existing coastline, by closing off all the river openings between the Westerschelde leading to Antwerpen and the Nieuwe Waterweg leading to Rotterdam. A real technocratic approach to things, which ran into trouble once the ecological impact of the closings became known. Hence why the Oosterschelde wasn’t dammed in the end, but got a storm surge barrier that’s normally opened, but closes during storm conditions, keeping the ecology of the estuary alive but still protecting against flooding.

Around the turn of the millennium the Deltaplan was largely completed and it seemed we were save from the water, but then it turned out we forgot about the rivers. The reason the Netherlands is a delta is of course because the Rhine, Maas and Scheldt flow into the sea here and with the more unpredictable weather and more frequent winter downpours, any access river water will ultimately flood here as well. We got a rough wakeup with a series of flood threats in the late nineties, which proved that the previous approach of just damming in rivers with no room for them to roam was no longer working.

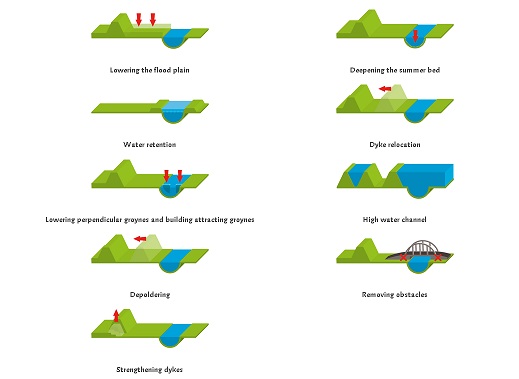

instead we got a nationwide approach on the lines of what the article descripes for Rotterdam: Room for the River. Create room for a river to meander and it has more room to absorb flood water. Counterintutitive for a country that has always prided itself on taming water, not working with it. And certainly there has been local resistance against e.g. deliberately returning a polder back to the sea. But on the whole the idea that climate change means more unpredictable weather and therefore more flood danger that needs to be defended against, is not controversial. And as a country we are rich enough to defend ourselves against such relatively simple dangers. The problem is that the more unforseeable dangers of climate change are still largely ignored and that for the past decades we’ve on the whole had more climate change skeptic than aware governments…

No Comments