Seventy years ago this day the worst disaster modern Holland would endure was on its way to the Dutch coast, to arrive that night in the form of storm swept waves overwhelming the coastal defences that for centuries had kept us safe. The results are seen in this video compiled of contemporary news broadcasts:

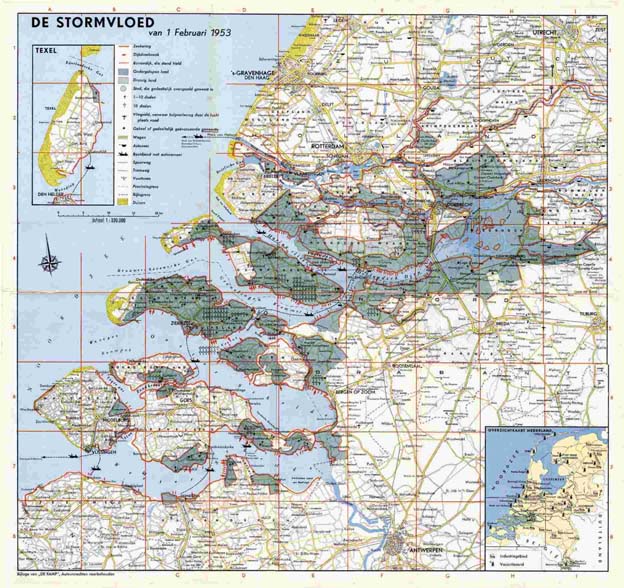

1835 people died, 750,000 people lost their homes, tens of thousands of cattle drowned alongside their owners. Whole villages, even whole islands swallowed by the water. The flood hit the south-west of the Netherlands, coming through the Channel into the North Sea, its narrow width pushing the water higher and higher until it hit the coast. On the map below you can see how the northern islands in the delta were hit the hardest, the water pushing its way into the mouths of the rivers Rhine, Meuse and the Schelde flowing into the sea there. This is land that has always lived with the threat of the sea, has been conquered from it, that thought itself safe behind the dykes created to protect us from the sea. What happened in 1953, the failure of the dykes to protect us is something that even now, seventy years later, still resonates in the Dutch psyche.

The reponse to the disaster is well known. Drastic measures were made to ensure that this disaster would never repeat itself. Instead of strengthening the existing dykes, something much more radical was done. If the delta was this vulnerable because of its long coast line, let’s just shorten this coast line by damming in the various channels. The idea was to close up all of them except for the routes towards Rotterdam and (grudgingly) Antwerpen. That this would be an ecological disaster was ignored; that it would destroy the livelyhood of centuries old fishing communities likewise. The country must be made safe and even if strengthening the existing dykes was good enough, it would also be far too expensive, so instead the cheaper option of damming up almost the entire estuary was chosen.

As the lesser inlets were dammed up one by one, the fishers and ecologists saw how much of a disaster it was for the wildlife and the fish in them as they became dead, brackish pools with little to no life left in them. I remember liking to swim in one of these blocked up inlets, the Veerse Meer, because there was never any chance of encountering anything icky like jelly fish, let alone any real fish. But for the fishers in Yerseke it was a sign. They were dependent for their jobs on an open Oosterschelde, which also was one of the richest wetlands in Europe, a natural treasure trove, full of wildlife including seals. That would all be lost if the Oosterschelde was to be closed, but the state, province and Waterstaat, the agency responsible for the dykes and water management were all firmly in favour of the closure.

Yet that one small village resisted. A group of fishers, enironmentalists and sympathisers started a resistance campaign. Their reasoning was simple. If the Westerschelde could be made safe by strengthening the existing dykes and be kept open, why not the Oosterschelde? With the former being the entry towards Antwerpen it made sense that it was kept open, while the latter was just not judged important enough for the expense. Thanks to their dogged resistance, their years long campaign to convince politicians, the public and scientists, the Oosterschelde was kept open and the Netherlands got one of the seven wonders of the modern world: the Oosterschelde Storm Barrier, the stormsvloedkering:

I was there when the Stormvloedkering was officially opened, in 1986, as two students from each primary school in Zeeland were invited to it. Back then the political struggle, the role the activists had played in forcing the government and Rijkswaterstaat to this compromise, was kept largely unmentioned. I remember it was all presented as just a normal change of policy, that it was a result of changing insights naturally arrived at by the state itself, not pressure from lowly fishermen and beardy weirdo environmentalists. The Storm Barrier as the ultimate symbol of progress and Dutch innovation, but had it be left to its own devices, an environmental holocaust would’ve happened. Thank god for those Yerseke oyster fishers!