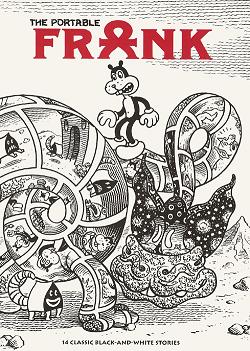

The Portable Frank

Jim Woodring

Fantagraphics, 2008

200 pages/$16,99

Get if from Fantagraphics.

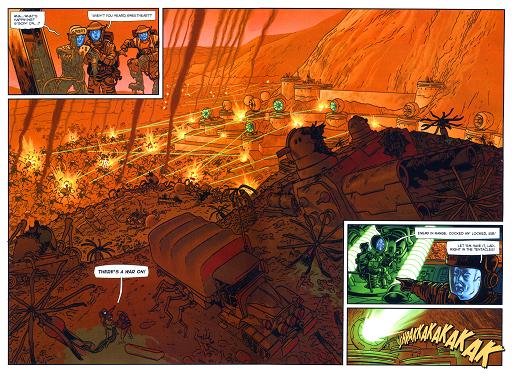

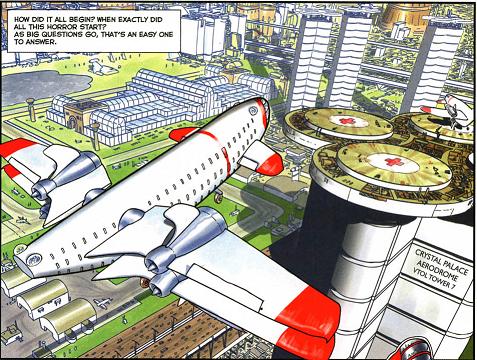

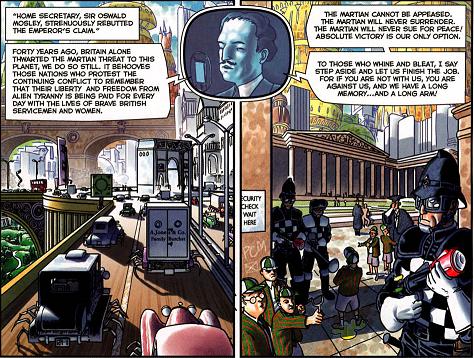

The Portable Frank is a collection of fourteen of the black and white Frank stories wrote and drew in the twenty-odd years since Frank first appeared on the cover of Jim issue four back in December 1990. Frank looks like a mutated Felix the Cat wearing Mickey Mouse’s shoes and gloves and even so is the most normal looking of the cast of characters Woodring assembled around him. Two words you’ll hear a lot when describing Frank’s adventures: dreamlike and surreal, as reviewers try to grapple with the world and cosmology Woodring has created with these stories. A copout, but it is difficult to explain Frank to people who haven’t seen these stories.

The best comparison I can make is to finding a collection of legends or fairytales from some unknown mythology. The stories make no sense together, sometimes contradicting each other, characters changing from one story to the next, dying in the one and returning with no damage in the next. At the same time you can see how this mythology must’ve developed over time, how each character has their role to fullfil in it. That’s what these Frank stories are like.

Frank himself is the innocent everyman, kindhearted, a bit naive but capable of shocking cruelty at times. His main nemesis is the manhog, half man, half pig, all rage and id. Manhog often attacks and bullies Frank, but as often is the victim of others, used and abused by the closest figure the strip has to a true evil personage, Whim, the moonfaced grinning devil figure, who acts as the tempter to Frank, warpinghim spiritually as well as physically. His servant (?) Lucky is a human looking figure, but with a hugely elongated face, usually seen manhandling Manhog for some menial task or other. As his protector Frank has Pupshaw, a dog kennel shaped creature with a sort of bushy raccoon-like tail, whom Frank takes for a pet in the first story. Pupshaw largely behaves as a sort of dog or cat like creature, but transforms herself into a monsterous form when needed. There are also Faux Pa and Real Pa, older looking, more heavyset and stubbly versions of Frank, who walk on four paws. Faux Pa, in league with Whim, turns up in several stories to try and transform Frank into something more cruel, while Real Pa only shows up in the last story, guiding Frank out of the dungeons he had landed himself in.

All of Frank’s stories are nearly wordless, told in pantomime, with no dialogue and only a few captoins here and there, usually at the end of a tale. What we see and get to know of the various character’s emotions and their inner life has to be deduced from their expressions and postures. Woodring is a master at this, in drawing attention to a character’s mood by showing it on their faces, slightly exaggerated but never forced. He also uses a lot of reaction shots, where in panel one something happens and in the next panel you see Frank’s reaction to it, acting as a counterpoint.

Woodring’s art is stylised and inventive, as can be seen at Fantagraphic’s official flickr stream. You can run through this book in an hour, but come back to it time and time again discovering new details. Woodring is one of those artists that make you sees the world through his eyes, where you can’t help but see his figures and poses everywhere you look.

As a collection, The Portable Frank is an effort to have an affordable introduction to Frank’s world, the title of course harkening back to Viking’s old collections like The Portable Mark Twain. The format is nice, slightly smaller than a regular comic book in dimensions, but some concessions had obviously to be made to keep the price low. So there’s no bibliographical material, no key to the characters (whose names never appear in the stories and I had to get from Wikipedia), there’s just the stories themselves. But that’s enough.