My Librarything collection currently has 8201 books listed. It’s not complete. it’s likely never to be completed as I buy books faster than I enter them. almost a quarter of them are ebooks. Those are not the problem. The problem are the six thousand physical books. Not to brag, but this is what you get for spending four decades reading and buying books: a house filled to bursting with them.

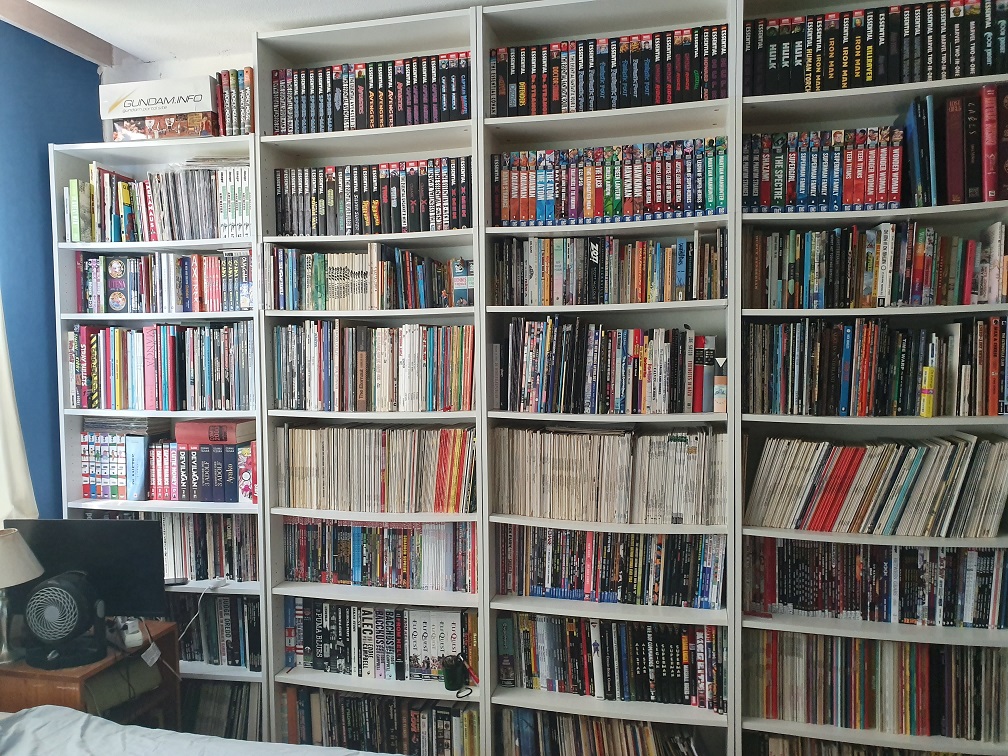

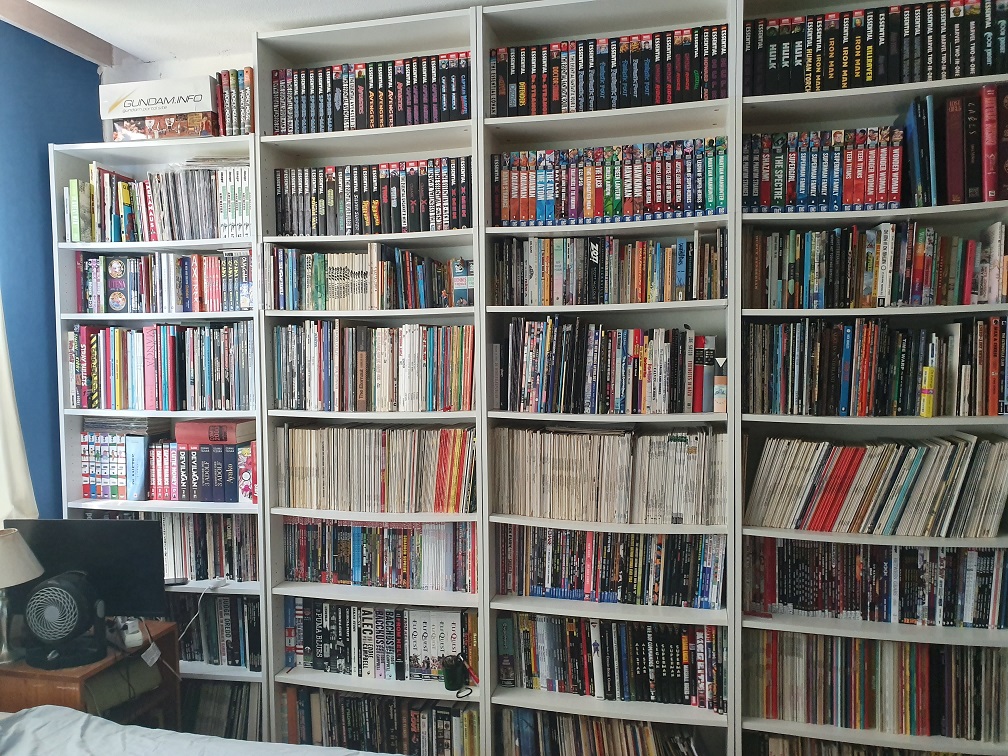

Which means my bedroom now has four of Ikea’s finest Billy bookcases in them. This is where I keep my physical graphic novels, European comics and manga. You may notice that the left most bookcase lacks an extension. For some reason Ikea slightly increased the height which made it just too high for my ceilings to fit a second extension. Really frustrating. Most of the comics here are European, with a lot of American graphic novels and trade paperback or hardcover collections as well. Most of my manga is digital: both cheaper and easier to store. Manga is also much more easier to read on tablet than European or American comics. Partially because they’re mostly in black & white, partially because the panels are bigger. It can be an exercise in frustration to read e.g. some eighties Marvel collection and having to zoom in to read the tiny tiny word balloons.

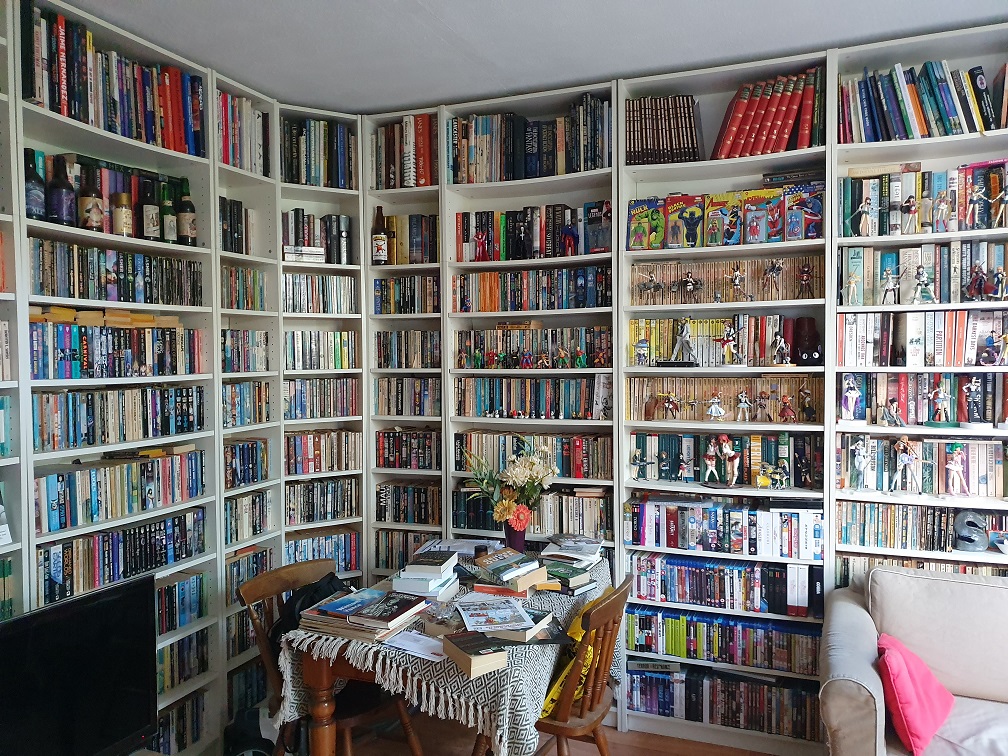

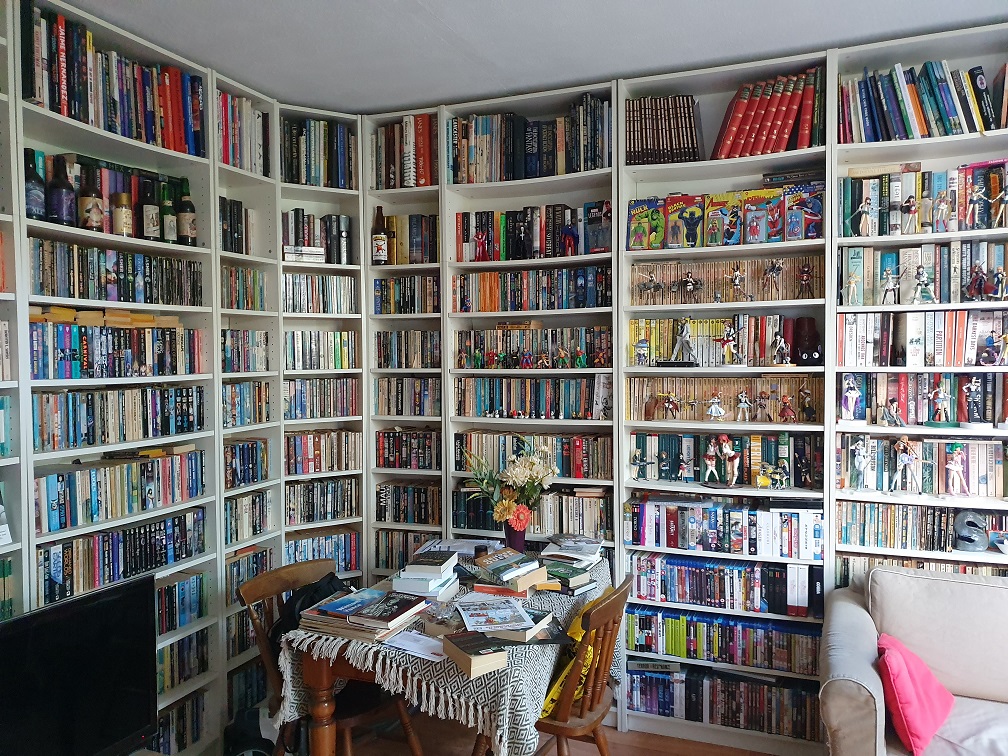

Looking from my kitchen into the living room, only part of the bookcases can be seen. They cover fully three quarters of my wall space. Starting from left next to the kitchen opening, all the way around the room to the back. Only walls not covered is the back wall which looks out at the garden and the bit of wall where my computer desk is. They’re mostly full now, as you may have noticed. You may have also noticed the overflow on the dinner table. The beauty of living alone is that you can use it to store your current reads and nobody will object…. To conserve space my books are sorted by size before genre. Paperbacks by paperbacks, hard covers on top, trades in the bookcases not visible here. Most of my fiction is in paperback, the most convenient format. Non-fiction is a different matter. As for what I read, science fiction/fantasy, crime novels and history are my most read genres. But if you want to really know, read booklog.

All of which is not even counting the floppies I also have. The eleven long boxes here are just the biggest part. Several more long boxes and crates are stashed elsewhere in my house, wherever there’s room. I spent roughly a decade and a half, 1987 to 2001 or so buying comics this way and it all adds up. The frustrating thing is that they’re barely accessible anymore because I just don’t have the room to open them.

Which is one of the reasons I’m looking seriously at moving out and back to my home town, where the houses are somewhat cheaper than over here. The other reason to be closer to my family and parents as they’re not getting any younger either. It would be great to find something where I could dedicate an entire room to my comics and not have to stash them in milk crates.