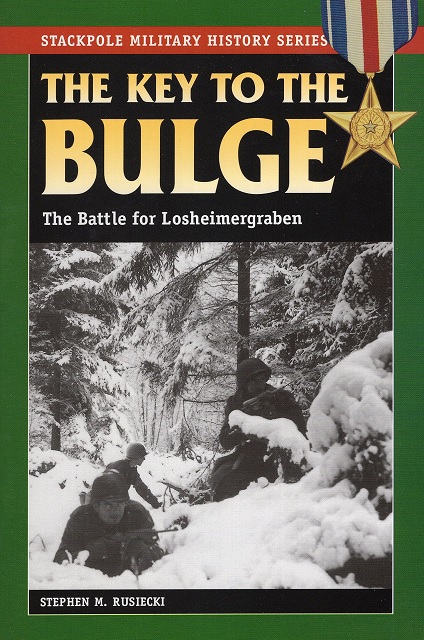

The Key to the Bulge: The Battle for Losheimergraben

Stephen M. Ruseicki

195 pages including notes

published in 1996

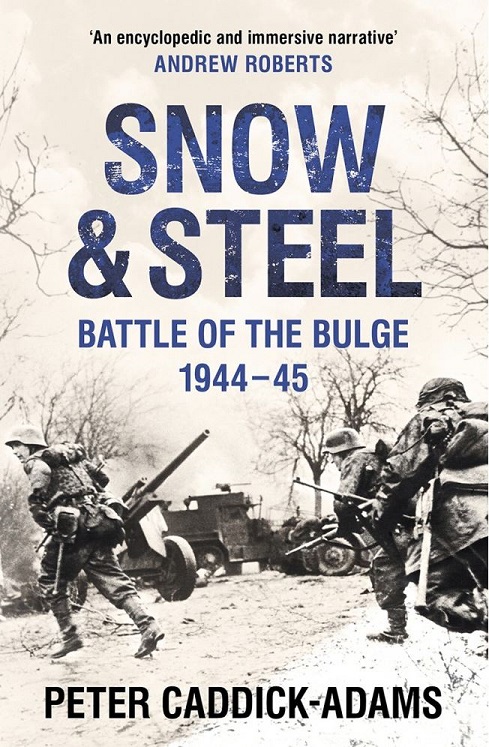

A visit to the Bastogne War Museum when I was on a holiday in the Ardennes last October got me interested in the Battle of the Bulge again, as did the series WW2TV did on the campaign in December. Their interview with Peter Caddick-Adams on 10 Facts about the Battle of the Bulge everyone should know led me to read his excellent book on the campaign as a whole. Which in turn whet my appetite for more on the individual battles within the Ardennes Campaign. Military history like all history is fractal after all. You can get a broad overview but if you zoom in you get a lot more detail, new insights. Which is where this book comes in. With Snow and Steel I got the broad strokes of the Ardennes Campaign, with this I got an overview of one of the most important of the early battles in it, one that could be argued determined the outcome of the entire Ardennes Offensive…

That battle was the battle for Losheimergraben, then, as now, a small border crossing between Belgium and Germany, too small even to call a village. In December 1944 this was the front line, the furthest point reached by the great Allied breakout from Normandy earlier that year. Since then the front line in the Ardennes had been largely static; the real fighting continued further up north, in the Netherlands and around Aachen. The Ardennes itself was quiet, an ideal sector to introduces green troops to life at the front and blood them before they got thrown into real battle. Losheimergraben and neighbouring places like Lanzerath were held by such troops, the 394th Infantry Regiment of the 99th infantry Division. It was these troops that would hold out for thirty-six hours against the Sixth Panzer Army starting on the 16th of December, denying it the quick victory it needed to comply to its already impossible schedule.