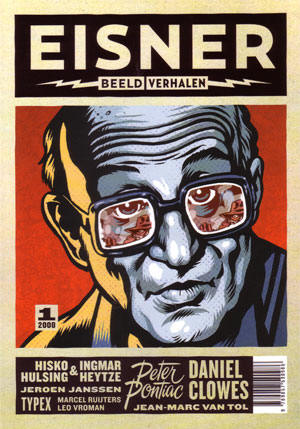

Eisner is a Dutch literary comics magazine founded in 2008 and published twice a year. So far five numbers have appeared, but there won’t be a sixth, as the publisher has pulled the plug. According to Michael Minneboo’s story (Dutch) even with a subsidy of 10,00 euro each for the first three issues sales never broke even. Eisner only managed to get around 250 subscribers, with about 1,000 issues sold to book and comics shops, though a lot fewer than that actually ever reached a reader.

A sad story for what, as far as I can tell from Michael’s post, seemed like an interesting magazine, an attempt to publish comics aimed at a proper literary audience rather than at grownup comics readers as classic comics zines like Titanic or Wordt Vervolgd (The Dutch edition of A Suivre) used to do in the eighties. As it turned out, this was much harder than it seemed and judging from the sales figures it never found its readers. The main question now is whether this is because that audience just isn’t there, or whether Eisner never was promoted properly to this audience.

One clue might be the first sentence in the previous paragraph. Michael Minneboo’s post was the first I heard about Eisner myself and if I’m not part of its target audience, who is? Somebody like me, who is or used to be seriously comics addicted, who no longer has collecting comics as a hobby, but rather reads comics like they read any other book, who doesn’t necessarily keeps up with comics news all that much but who would try a magazine like this if they stumble across it. Yet Eisner never reached this audience because I never knew about it, so it must have done something wrong..

That is the best scenario I can think of. The worst scenario is that there just isn’t an audience for good comics, or “graphic novel”s as we’re supposed to call grown up comics in the Netherlands now. It might just be that the sales success of a select few “graphic novels” was a fluke, that Persopolis or Logicomix sold so well because of their subject matter and a media hype rather than because these tapped a new literary audience that would be interested in more “graphic novels”. The flood of inferior comics packaged as “graphic novels” won’t have helped either in this regard.

Quite likely the truth lies somewhere in the middle: a magazine that only appears twice in a year and is fairly expensive (fifteen euros per issues) isn’t perhaps the best way to get potential new readers to sample the delights of comics. If you only appear once every six months you get lost in the flood of magazines and you need to keep publicising your existence. The price meanwhile, though obviously needed to break even, is too high for an impulse buy. So it had two strikes against it already, which need excellent p.r. and a bit of luck to find an audience that looks to be smaller than the sales of the few bestselling graphic novels might lead you to expect.

And of course most magazines, comics or otherwise, fail.