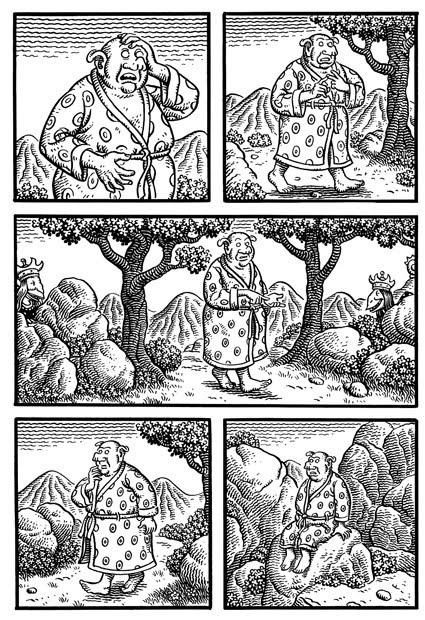

I’ve talked about Jim Woodring before in my Friday Funnies series. Weathercraft is the newest book in his Frank series. As always, it’s a nearly wordless comic, no dialogue, no captions, just art. Reading it can be done in five minutes, you’ll be able to follow the story from panel to panel, from page to page, but you’ll have no clue as to what just happened. I’m a text orientated guy, I read comics text first, art second and I did read Weathercraft that way first, fast, just getting the bare bones of the story, following it panel to panel, page to page but without taking in it as a whole.

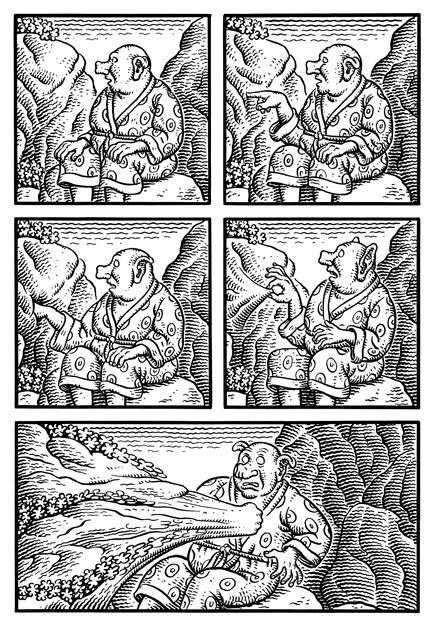

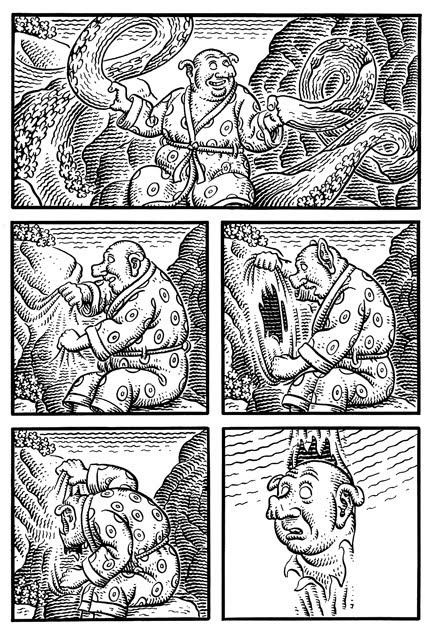

This naive way of reading any Frank story comes natural, thanks to Woodring’s art. There’s nothing difficult or unclear about his artwork, as you can see from the page above. For the reader, the hard work does not lie in following the story from panel to panel, but in coming to some understanding what the symbolism in the story could mean, whether it is representing some deeper meaning or is meaningful of its own accord. For Woodring, the hard work must lie as much in making things so clear to the reader, to making Manhog’s expressions so easily readable, to keep the flow of the story obvious especially when the symbolism grows heavy.

Such as it starts to do here, as Manhog discovers the plasticity of what seemed until now be a solid reality. As might be obvious by now for readers already familiar with the universe in which the Frank take place, the unifactor, this is a Frank story in which Frank is only a secondary character and Manhog is trust into the lead role. His transformation and edification as to the true nature of the Unifactor, the universe in which he lives, is the story of Weathercraft

But what this story is, what Manhog’s investigations reveal, will remain a secret for now. It’s pointless trying to recap it here. More perhaps than any other comic, the pleasure in this lies not with its plot revelations, but with the flow of the story. You do not even need to attempt to understand What It All Means, just reveling in the worlds Woodring has created here is pleasure enough.

For those who still want to know at the very least what Woodring thinks it all means, there’s his video walkthrough over at Fantagraphics. Personally, I find ignorance is bliss in this instance.