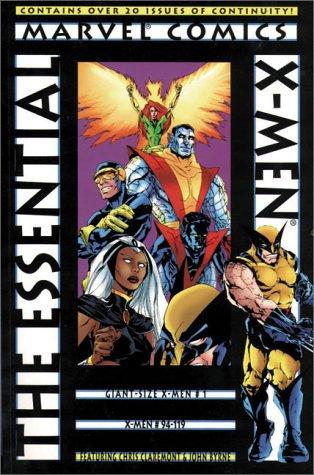

Essential Essential X-Men Vol. 1

Chris Claremont, Dave Cockrum, John Byrne and friends

Reprints: Giant-Size X-Men #1, Uncanny X-Men #94-119 (July 1975 – March 1979)

Get this for: the start of the X-Men revolution — four stars

Hard to imagine now, but once upon a time The X-Men were a failure, never having been more than a cult hit throughout the Silver Age, even becoming a reprint series with #67. It limped along for a couple of years, up until issue 93, while the team showed up here and there as guest stars in other titles, some members becoming Champions, well The Beast had his own solo series in Amazing Adventures before joining the cast of The Avengers. It all seemed over for the X-Men, but like good superheroes they came back in the nick of time and it all started with Giant-Size X-Men #1, the first issue reprinted here.

Giant-Size X-Men was followed by a renewed X-Men series, started with #94. While these first two issues were written by Len Wein, by #95 Chris Claremont had come aboard and he would remain the X-Men’s writer for some seventeen years. It takes him a while to find his voice and the first few issues are on the rough side, but it really doesn’t take long for the mutant juggernaut to start rolling. Claremont’s writing on X-Men revolutionised superhero comics and it’s here that it started: by the end of the volume the classic Claremont is established.

Some elements of it pop up even earlier. Both the most loved and hated characteristic of Claremont’s style is having long, drawn out plots and subplots, stacked on top of each other, with one menace fading into the background earning the heroes only a little respite before the next one, long foreshadowed, has to be fought. Here Claremont starts doing this as early as #96-97, the first of which foreshadows the return of the Sentinels, with #97 introducing the menace of Eric the Red, while Prof Xavier was plagued with strange dreams of a Galaxy far, far away. The first threat takes until #100 to be resolved and of course leads to the metamorphosis of Marvel Girl into Phoenix, which comes in handy for defeating the second villain, who turns out just to be a pawn of a mad emperor of the alien Sh’iar Empire, who in turn threatens to unleash the end of everything. It all gets fixed by #108.

Said issue incidently features something I wish was still used in modern Marvel stories, the half page or full page looking in at the rest of the Marvel Universe while the heroes of the comic you’re reading are struggling to defeat the menace du jour. In this case you have Peter Corbeau onboard the Sunwatch space station briefing Mr Fantastic of the Fantastic Four, Beast and Captain America of the Avengers as well as then president Jimmy Carter via teleconference, explaining that yes, the strange blip felt at the end of the last issue was indeed the entire universe ceasing to exist for half a second and that if it happens again, the universe may not come back… This kind of scene always helped emphasise the seriousness of a threat, that it was not just the X-Men’s fate that mattered, but everybody’s. But it also helps build up a sense of interconnectness, that these adventures are not taking place in a vacuum.

From the start the X-Men are kept busy here; there are no quiet issues. After establishing the new team and sending them on their first mission in Giant-Size X-Men, they immediately have to defeat Count Nefaria’s threat of nuclear annihilation in the next two issues, deal with the death of a teammate, fight the sentinels over multiple issues, see Professor Xavier deal with futuristic nightmares, deal with old enemies gunning for them, first Black Tom and the Juggernaut waiting for them in Ireland, only defeated with the help of leprechauns (not their finest houre), then Magneto returns, but their fight with him is cut short as they’re swept up in the intergalactic adventure mentioned above. Once finished with that, Wolverine has to deal with the Canadian government wanting him back, before yet another old enemy turns up and makes the X-Men into funfair performers. The Magneto turns up again, kidnaps them to his secret base near the Savage Land, which blows up and leaves two sets of X-Men, as the Beast and Phoenix manage to return home, while the rest helps Ka-Zar fight a would be conqueror in the Savage Land, before being picked up by a Japanese vessel who drops them off in Japan just in time to fight Moses Magnum, which ends the volume. It’s all fastpaced and incredibly busy, but Claremont always remains in control and keeps things understandable.

He’s helped in this by the art, which from Giant-Size X-Men #1 up to X-Men #107 is in the hands of Dave Cockrum, with the rest of the issues drawn by John Byrne. Quite different artists of course, with Cockrum having a much looser, cartoony and swashbuckling style, lending itself well to widescreen space opera, while Byrne is more realistic in his art. Byrne is also one of those artist who, like Jack Kirby have the effect on me that if I read a large run of their stories in one go, I start to see the world through their art. So now suddenly everybody on tv is standing around in those typical widelegged, slighty skewed Byrne poses… Both Cockrum and Byrne are wonderful artists here, well suited to Claremont, who adapts his stories to their strengths. Of the two I prefer Byrne, just because he does things for me Cockrum can’t.

Sadly, some of Claremonts more annoying tics are also in evidence here, especially in the characterisation. There’s a lot of ill established antagonism between characters, which especially in the earlier issues was wearisome. There are also the first glimmers of another bad Claremont habit, the subtle and not so subtle references to the past lives of some of the X-Men, especially Wolverine. Some idiot plotting as well, where Claremont goes for the “make life more complicated for the characters through bad communication and drawing out of misunderstandings”. It’s bearable here, but I do remember at the end of his X-Men run, when it just became too annoying.

One other complaint I had was the misuse of Jean “Phoenix” Grey. Supposedly the most powerful person on the team, story after story has her being taken out easy or struggle to defeat villains she should have been able to take with one arm tied behind her back. The same goes for Storm, though to a lesser extent. Also very powerful, she again is kept out of action more than she should have been. If you have strong female heroes, use them, don’t find contrived ways to keep them out of action to keep the story going for longer…