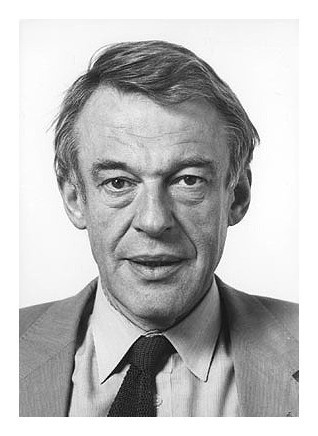

The news had resigned his position as leader of the PvdA (the Dutch Labour Party) came as a bolt out of the blue. He had given no previous indication of being tired of his job, nor had there been any pressure on him to resign. The local elections last week had seen his party, if not win, at least limit its losses and in the national polls the downward trend seemed reversed as well. In no small part this was due to the PvdA’s refusal to agree to another extension of the Duch occupation in Afghanistan and subsequent collapse of the CDA-PvdA-Christenunie coalition government, which had re-energised the party’s base and played well with those voters who had left it for the SP, the Socialist Party, back in 2006. So why did Bos resign, when he had managed to lead the party so well, especially knowing how despised and weak it was when he took over in 2003.

The official reasons he gave was that he wanted to spent more time with his wife and family, that the long hours and pressure of politics had taken its toll and he wanted to step back. It’s certainly true that he has aged a lot in the past two years or so. Nor is he the only prominent politician to announce his retirement for these reasons – Carmiel Eurlings, one of the youngish up and coming talents of the CDA had done it the day before.

But as any fule knows, you should never trust a politician’s reasons for retirement, especially when they give their families as the reason why. Nobody becomes a politician to built a good family life, but you can certainly decide that the work-family balance needs to be altered if the job has lost its glamour and the work got harder. And if there’s one thing that’s certain, after the upcoming elections the job will get a lot harder.

Because there never has been a time when the Dutch electorate was as divided as it is now, or the parties as far apart. CDA and PvdA for obvious reasons can’t get back together, certainly not with Balkenende remaining the Christian Democrats’ leader, though it helps that Bos is resigning. A leftwing government of PvdA and SP is impossible because even with one or two of the other leftwing parties like GroenLinks or even D66 they won’t have enough seats. A straightforward rightwing government, the rightwing liberal VVD joining CDA runs into the same problems, while the elephant in the room is Wilder’s PVV. Wilders is supposed to become the big winner of the June elections, his party on track to become the third-biggest party in parliament and therefore in a key position for coalition negotiations.

The problem is, Wilders doesn’t really want to be in government — his entire schtick is based on being radical and uncompromising, being in government undermines that completely. PvdA meanwhile has already ruled out being in government with them anyway, while other parties are also weary. It all mkaes for quite a headache for whoever gets the task of preparing a government after the election, with no clear coalitions possible yet. Government is going to be a hard slog, knives in the dark stuff, bad compromises and betrayals. No wonder Bos let this opportunity pass…

That Bos’ announcement, while surprising, wasn’t completely unexpected at least in his own party, came slightly later today, when the current mayor of Amsterdam, Job Cohen, announced his bid for the leadership of the PvdA, which he is reasonably certain he will win. Cohen has bee asked before to fullfil a role in national politics when Bos suggested he could become prime minister if the party won the elections back in 2003. Then he wanted to stay in Amsterdam, now he’s ready to do so. A good choice he would be to, having a national profile as a well liked and respected mayor amongst voters of all parties. He has a reputation as a bridgebuilder and appeals to those voters who are repulsed by Wilders and his histrionics. It will also help that he hasn’t been involved in the last government of course, to repair relationships with the CDA…