One Magemanda isn’t keen on the current attention given to the continuing gender imbalance in science fiction, claming so totally NOT on board with this focus on women in literature:

1) In any other workplace, if people were determined to focus on the specifics between men and women, there would be a good case for a charge of sexism.

2) Women have been fighting for equality for years: why is this suddenly a new story?

3) In chick lit, there is not a fierce desire for there to be a slew of male authors – no one argues that Mike Gayle should be as widely read as Marian Keyes. Authors are enjoyed on their own merits.

4) Last night I was watching the Great British Menu and the commentator described one of the judges as a top female chef – and I felt insulted that she wasn’t just considered to be a top chef. The same can be applied to authors: we should be insulted at having to focus on women separately.

For me, this is the height of a storm in a teacup, and I’m so tired of hearing about it now.

Why not consider it this way:

Read the books you like. Enjoy the books you read. Who cares the sex of the authors writing them? I certainly don’t! Do you?

A naive and ill thought out response perhaps, but one that needs to be answered. I suspect there are quite a few science fiction readers who likewise don’t get what the fuss is about and wonder why they should care about “the sex of the authors”. You cannot force people to care about the political implications of their entertainment choices; you’ll have to convince them. Magemanda’s post offers a good opportunity to do so.

The reason why feminism and the continuing gender imbalance in science fiction has gotten back on the agenda is simple: the death of Joanna Russ. An outspoken feminist icon and writer, her death and the renewed focus on her work that it inevitably brought made painfully clear how little has changed since she first criticised science fiction for ignoring its female writers. And while there had been a renewed interest in making science fiction more inclusive these past few years, Russ’ death was the catalyst that spurred people to action.

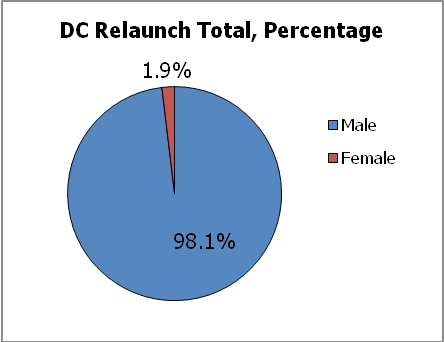

So, no this is not a new story, but that doesn’t matter. It’s still important. Science fiction suffers if we ignore half the people writing it. But last year several of us discovered this was exactly what we had been doing by “enjoying the books we read and not caring about the sex of the people writing them” and –surprise surprise– discovering the overwhelming majority of writers were male. By reading on autopilot, I missed quite a bit of good science fiction written by people not on my radar. I needed to consciously think about the kind of authors I wanted to read to redeem my mistakes. That’s why even as a reader it pays to look at what you’re reading, to make sure you’re not missing books you’d enjoy just because their author isn’t part of your usual circle.

Reading between the lines, I got the impression Magemanda thinks projects like Ian Sales’ SF Mistress Works is about separating out the women from science fiction, putting them in a separate league like with womans’ sport. But this is not the intention at all. We I think we’ve proven by now is that if we don’t make a fuzz about female writers, especially as male readers and reviewers, we run the risk of forgetting about them, of neglecting them. That’s why we need to pay more attention to female writers, even if in an ideal world the gender of a writer shouldn’t matter.