Do not complain when at last you become quaint and old-fashioned, when you grow as outworn as the crinolines of a generation ago and are classed with Spicy Western Stories, Elsie Dinsmore, and The Son of the Sheik; do not mutter angrily to yourself when young persons read you to hrooch and hrsh and guffaw, wondering what the dickens you were all about. Do not get glum when you are no longer understood, little book. Do not curse your fate. Do not reach up from readers’ laps and punch the readers’ noses.

Rejoice, little book!

For on that day, we will be free.

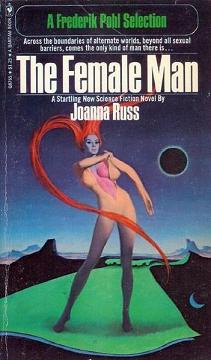

The quote Patrick Nielsen Hayden opens his in memoriam post for Joanna Russ with. It’s a quote that has been going through my head as well, ever since I read The Female Man last month. It was only then that I realised how important and how good a science fiction writer Russ had been. Most of her best work had been written long before I was old enough to read science fiction and once I was reading sf, she already had had to give up writing altogether because of medical problems… Not to make it al about me, me, me but there is something sad about only appreciating a writer just weeks before she dies.

Joanna Russ’ importance to modern science fiction is hard to overstate: The Female Man is not quite the first explicitly feminist science fiction novel, but it was the breakout one. It emphatically challenged the boys club atmosphere of science fiction and while the dream in the quote above hasn’t quite been fulfilled yet, thanks to Russ and the people she inspired one way or another, science fiction has become a lot less sexist than it would’ve been otherwise. After The Female Man it was no longer necessary for female science fiction writers to become “one of the boys” to be taken seriously.

But there’s more to Russ than just the one novel: The Adventures of Alyx, an early series of short stories and one novel about a Bronze Age girl kidnapped into the far future and making a living as a survival expert. Alyx is a precursor and role model to all later female sf heroes, from Ripley to Tank Girl to Buffy. Then there’s We Who Are About To…, a novel about a group of stranded colonists and the refusal of the one woman amongst them to play along in the others’ games about restarting civilisation: “Civilization’s doing fine,” I said. “We just don’t happen to be where it is.” There are her other novels and short stories, at least one of which, “When it Changed“, a companion story to The Female Man, is available online.

And then there’s her non-fiction, which contained the same feminist concerns that animated her fiction, the most well known being How to Suppress Women’s Writing, a collection of essays exploring just how female writers are shoved behind the curtain by the male guardians of the literary canon. Some of her non-fiction is available here.

Add it all together and you know why Joanna Russ was such an important writer; unfortunately she was also a writer easy to ignore, almost invisible if you don’t search her out on your own. Her influence is everywhere in modern science fiction, but that just makes it harder to see. Her enforced silence in the last two decades exacerbated this, which she talks about in this interview with Samuel Delany at Wiscon 30. This obscurity should not blind us to the woman we’ve lost this week: Joanna Russ was one of the giants of science fiction and we’re that much the poorer for her loss.