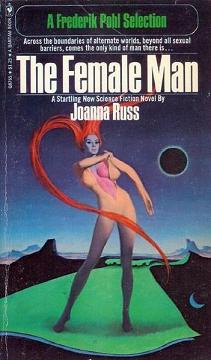

The Female Man

Joanna Russ

214 pages

published in 1975

The Female Man is the third book in my list of works by female sf authors I’ve set myself as a challenge to read this year. Of the books on the list it is the most explicitely feminist one, a cri de coeur of “second wave feminism”, a science fictional equivalent of The Feminine Mystique. Written in 1970 but only published five years later it was somewhat controversial, science fiction never having been the most enlightened genre in the first place. Reading it some thirtyfive years later it’s tempting to view it as just a historical artifact, its anger safely muted as “we know better now” and accept the equality of men and women matter of factly, its message spent as sexism is no longer an issue, with history having moved on from the bad old days in which The Female Man was written.

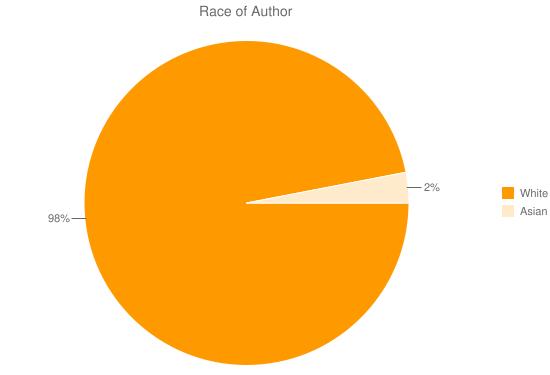

Bollocks of course, but seductive bollocks. The reality is that for all the progress made since The Female Man was published, its anger is not quite obsolete yet, or we wouldn’t have had the current debate about the lack of female science fiction writers in the first place. What’s more, The Female Man ill fits in this anodyne, whiggish view of history anyway. Russ is much more angry than that. She’s utterly scathing in her view of men in this novel, reducing them to one dimensional bit players: thick, macho assholes her much more intelligent heroines have to cope with. You might think this “hysterical”, “shrill”, “a not very appealing aggressiveness” but Russ is ahead of you and has included this criticism in her novel already, on page 141: “we would gladly have listened to her (they said) if only she had spoken like a lady. But they are liars and the truth is not in them.” Russ was too smart not to understand that no matter how non-threatening and “rational” The Female Man might have been written, (male) critics would still call it emotional and not worth engaging. But Russ uses her anger as a weapon and tempers it with humour and some of the angriest, bitterest scenes are also grimly witty.