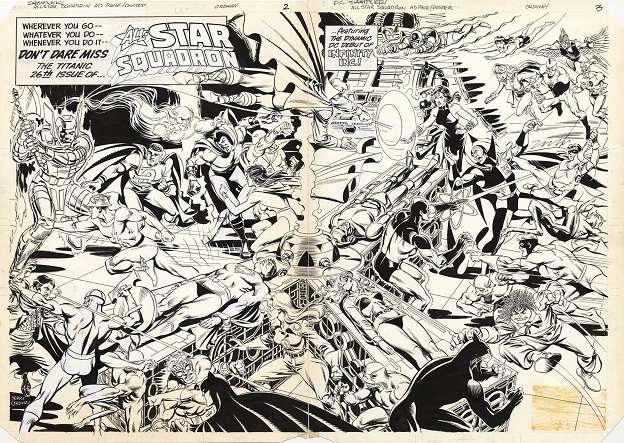

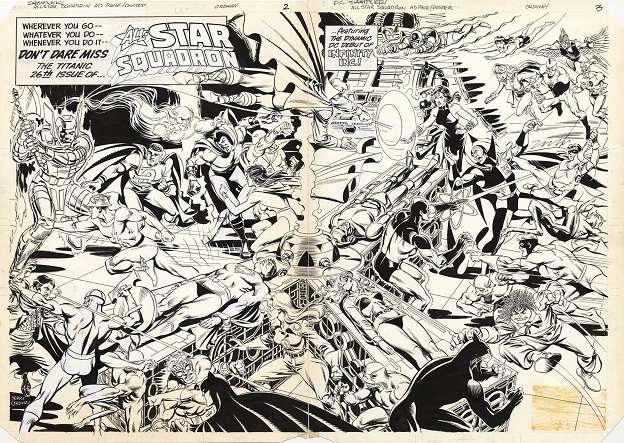

It’s hard to believe, but eighties and nineties DC Comics mainstay Jerry Ordway explains isn’t getting any work from them anymore and can’t live on the royalties for his older stuff:

On a recent Absolute Infinite Crisis hardcover, I had 30-odd pages reprinted in there, a book that retailed for over a hundred dollars– a book that DC never even gave me a copy of, and the royalty amounted to a few dollars, I couldn’t buy a pizza on that windfall. I want to work, I don’t want to be a nostalgia act, remembered only for what I did 20, 30 years ago.

In a way, Ordway is lucky. He at least still gets some royalties. Had he worked on Disney comics like Don Rosa, the most popular Donald Duck cartoonist after Carl Barks, he wouldn’t have received any royalty at all, as Rosa made clear in his explanation as to why he stopped drawing:

Disney comics have never been produced by the Disney company, but have always been created by freelance writers and artists working for licensed independent publishers, like Carl Barks working for Dell Comics, me working for Egmont, and hundreds of others working for numerous other Disney licensees. We are paid a flat rate per page by one publisher for whom we work directly. After that, no matter how many times that story is used by other Disney publishers around the world, no matter how many times the story is reprinted in other comics, album series, hardback books, special editions, etc., etc., no matter how well it sells, we never receive another cent for having created that work. That’s the system Carl Barks worked in and it’s the same system operating today.

For a time back in the eighties and early nineties it looked like (American) comics as a field would evolve beyond it’s low rent, exploitative roots and start treating its talent better. But that needed a growning, not a stagnating field and while comics have always been dying, never more so than in the past two decades. Working for the mainstream, commercial comics publishers in the US was always a good working class sort of career, where you could make decent money if you worked hard and were reliable, but were never going to get rich from. Nor would you get a pension from your work or anything other than a flat rate, but at least you’d still might be able to support yourself even after retirement with freelance work.

But when the slow collapse of the comics industry was accelerated with the mid-nineties crash, when the speculators and collectors left the field and superhero comics became what it was always destined to be, a niche market, it meant there were far too many cartoonists for the field to sustain and all the old pros, some having worked decades for the same company, would gradually disappear, retire, retrain, the lucky ones doing reproductions or sketches at comics cons to get some money, but many of them, like Jerry Ordway, finding it harder to make a living from what once seemed a safe job.

In some ways then what’s has happened to the commercial comics industry is a belated echo of what happened to so many American industries no longer needed or done cheaper elsewhere. These days there is still a comics industry, but outside the rotting corpses of the socalled Big Two it’s a much more boutique approach, one aimed at a smaller audience willing to pay more for a particular cartoonist’s vision or for excellently curated collections of the best of American comics history, with little room for those professionals for which comics was always more of a vocation than a personal calling. There’s no call for assembly line workers when you’re building cars by hand.