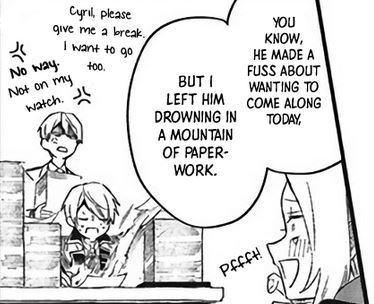

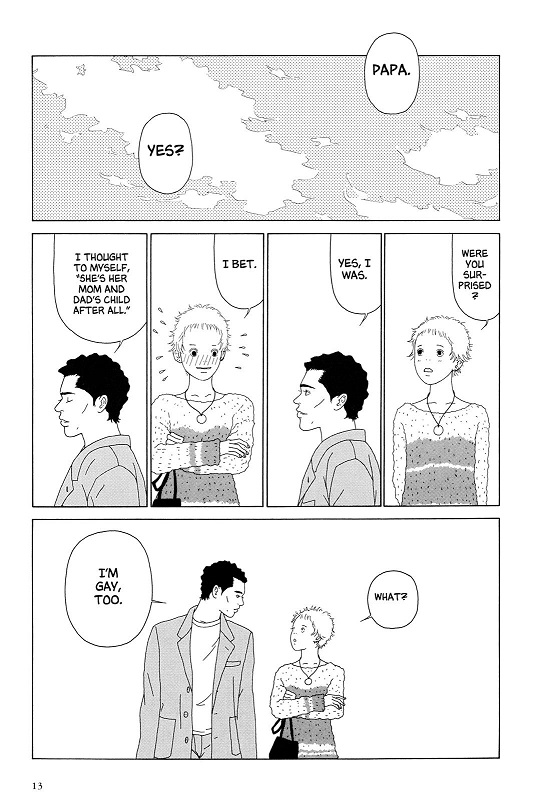

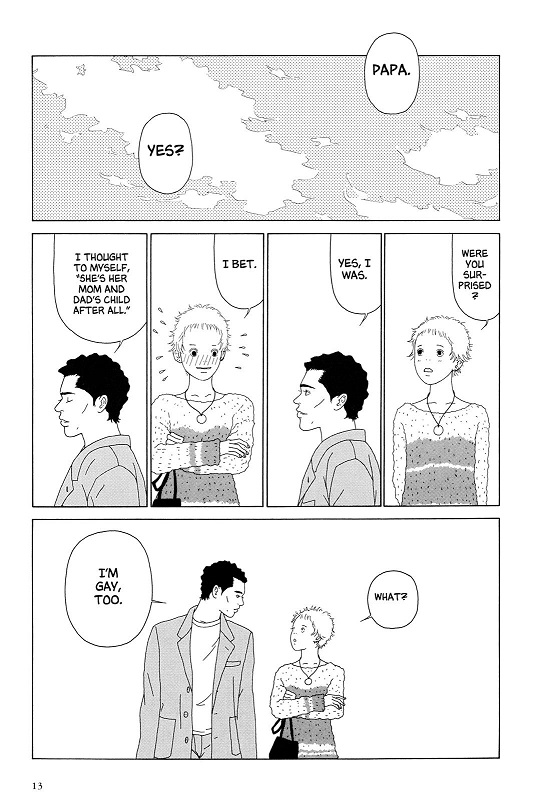

Yamaji Ebine’s Love My Life starts with Ichiko Izumiya coming out to her father as a lesbian, only to have the tables turned on her:

As it turns out, Ichiko’s father and deceased mother were both gay, best friends and decided to raise a child together. Her mother had asked her father never to mention this, but now she herself turned out to queer herself, he saw no reason not to. And while they were married and living together, they each still had their other, gay lovers. Coming out is difficult enough already, but having to also digest your parents’ own secret gay history must be doubly so.

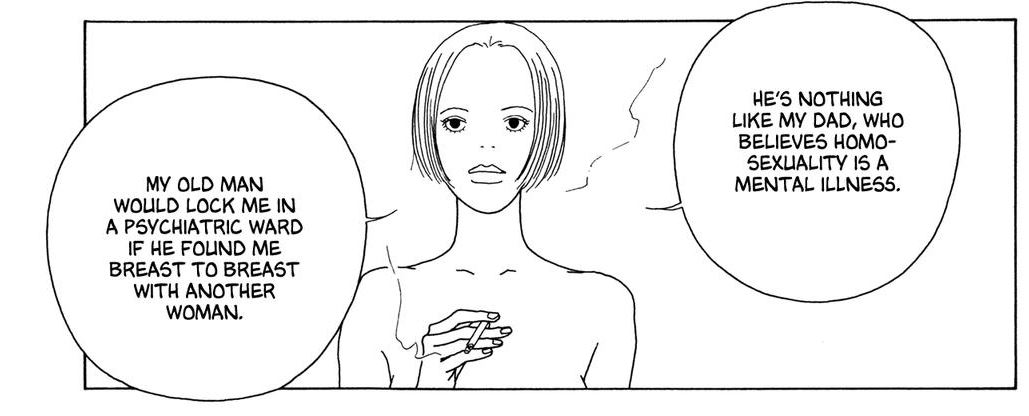

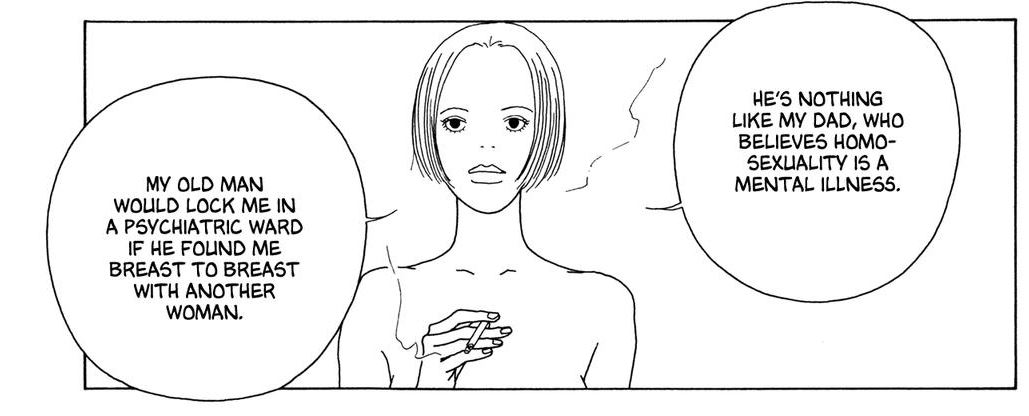

Processing the realities of her father’s gayness is just one of the things Ichiko has to wrestle with in this twelve chapter, single volume story. Eighteen years old, Ichiko is in her first relationship with Ellie Jyojima, three years older than her, a college student studying law. Unlike Ichiko, Ellie has been in several relationships before, both with men — before she realised she was lesbian — and women. Ellie is less fortunate than Ichiko, coming from a traditional family with a father who finds homosexuality “a mental illness”. The realities of having to deal with homophobia and the need for people to stay in the closet to their family, friends or work is a red thread through the story. It’s not just Ellie having to deal with hiding her queerness from her father or when running across a male ex-lover by accident, but also the more mundane realisation that people would see them as just friends when going out together.

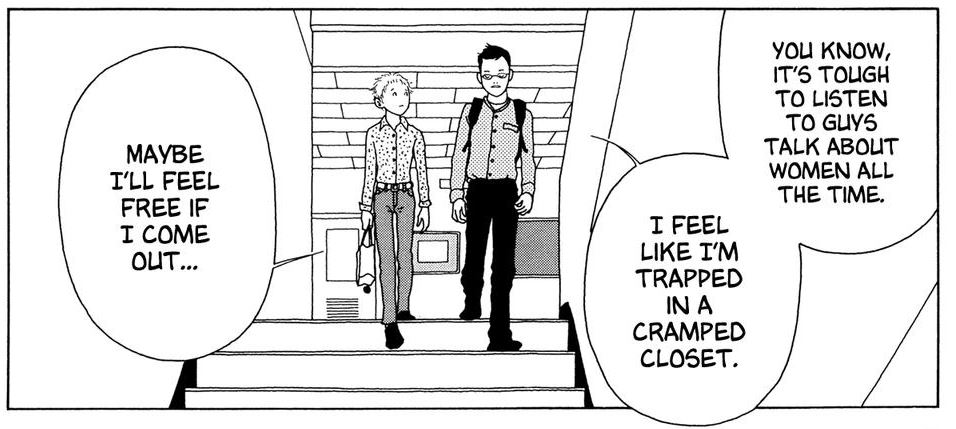

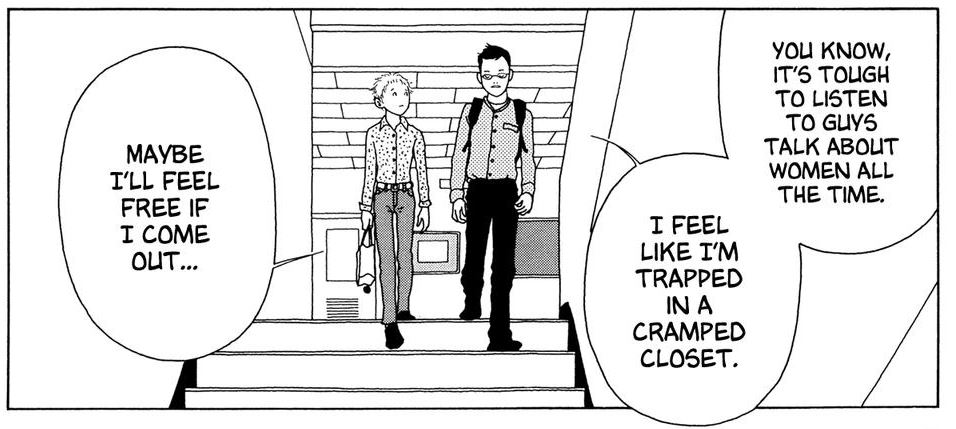

Or, the other side of the coin, people gossiping in college about Ichiko and Take-chan, a gay male friend, as obviously going out because they spent time together. He feels frustrated, trapped at being made to play the role of a straight man, but also doesn’t feel courageous enough to make that step out of the closet. Having overheard how people talk about gay men, he’s in no hurry to leave its safety and who can blame him. Instead he shares his frustrations and concerns with Ichiko, who does the same with him as well as her girlfriend. I like their friendship, that sort of outsider allyship that is quite common among queer people, sharing the same sort of experiences living in a heteronormative society. In general it’s good to see more queer people inhabiting this story than just Ichiko and Ellie. Take-chan, his boyfriend, as well as Ichiko’s father’s boyfriend, the old girlfriend of her mother Ichiko runs into, now in a new relationship, even a bald headed girl Ichiko has a short crush on in a later chapter, all drift and out of the story as required, all adding to the verisimilitude of it. This not some fantasy world where everybody is queer, nor the sort of story where only the protagonist and their love interest is.

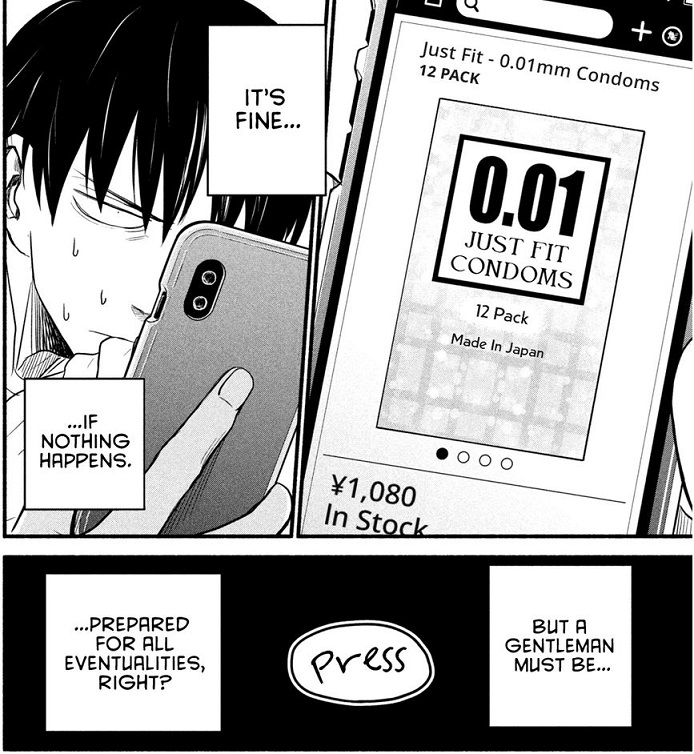

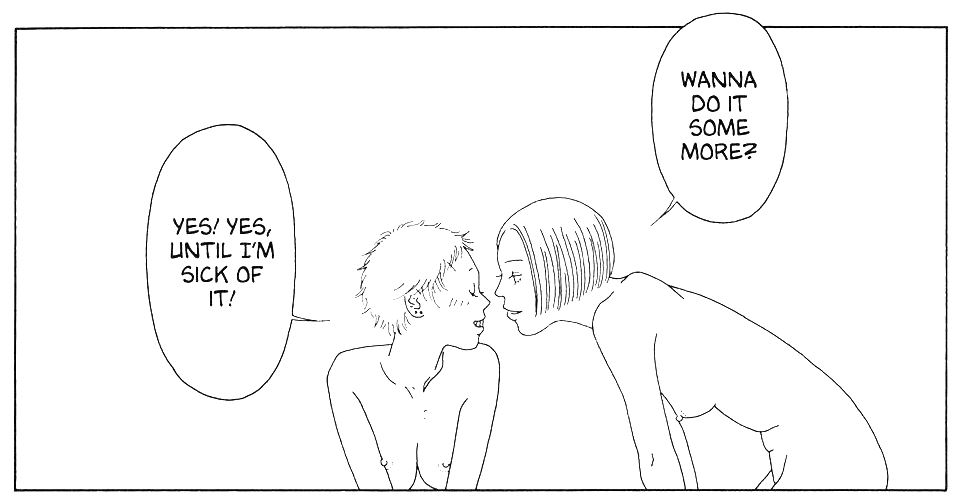

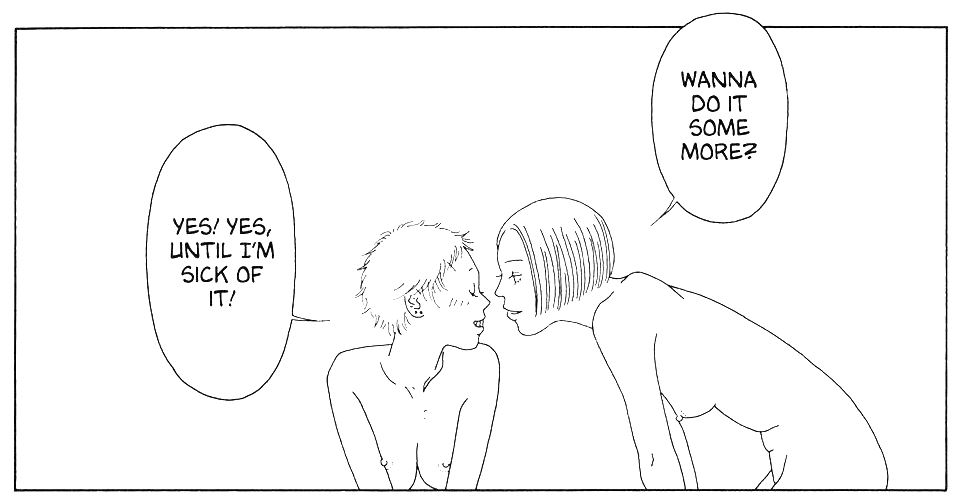

What also adds to the realism of Love My Life is that Ichiko and Ellie have a healthy sex life. It’s established from the start that they fuck and they like it, that part of their attraction to each other is physical and neither is embarrassed about this. It’s a refreshingly adult take that never felt exploitative or done for the sake of fan service. It’s refreshing when so many yuri manga are about high school romances where hand holding is the worst the characters get up to.

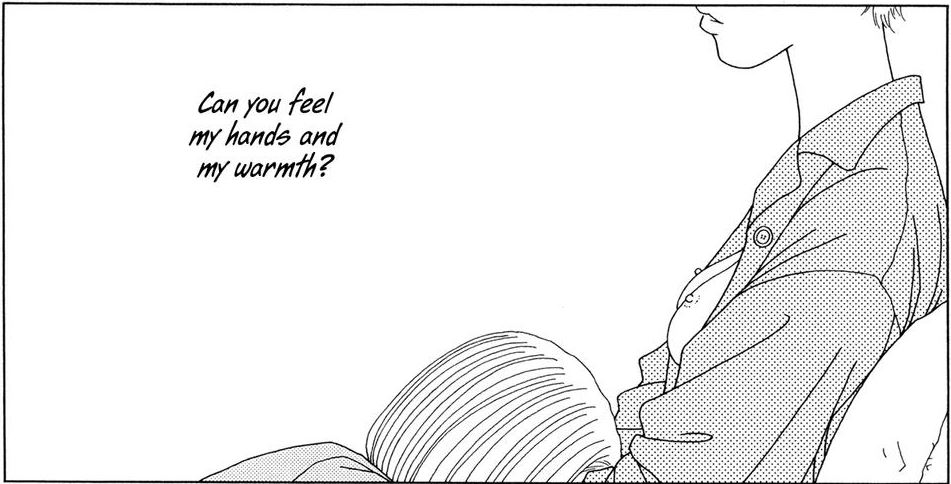

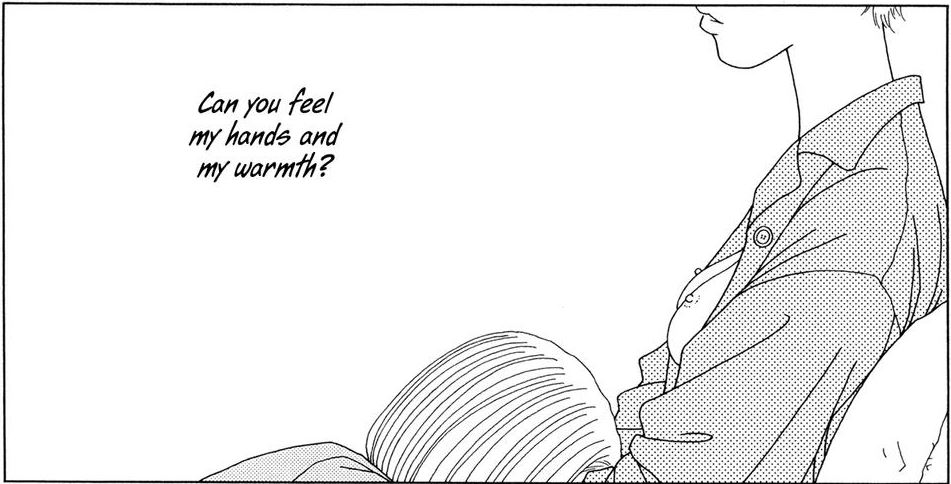

This is a very dialogue heavy manga as you may have figured out, but Yamaji Ebine’s art should not go unmentioned. With such a personal story it’s unsurprising that most of the art’s focus is on the characters, rather than the world they inhibit. Backgrounds are often left out when unnecessary, only when it’s necessary to establish a location do we get establishing shots, more functional than artistic. There aren’t the exaggerated emotions, few if any of the comedy deformations you might expect from a manga. Yamaji Ebine has a knack of nailing a character’s look with just a few lines: of course the driven, law student Ellie would have an almost Patrick Nagel-esque, sharp hairstyle. Of course the more sheltered and naive Ichiko looks a bit more fluffy in both hair and body.

Love My Life was serialised in Feel Young, a monthly magazine aimed at young women, in 2000 and 2001 before being released as a single volume manga. According to the afterword, Yamaji Ebine “this is where I began my career”. Although she had debuted several years before, she had stopped creating manga until Ichiko popped fully formed from her mind while reading a book by a female American writer. As far as I’m aware it has never been officially translated in English. Currently the only way to read it in English is through Mangadex. I hope somebody (Seven Seas?) does pick it up at some point; this is too good to languish in obscurity overseas.