Two perspectives. Larry Niven’s:

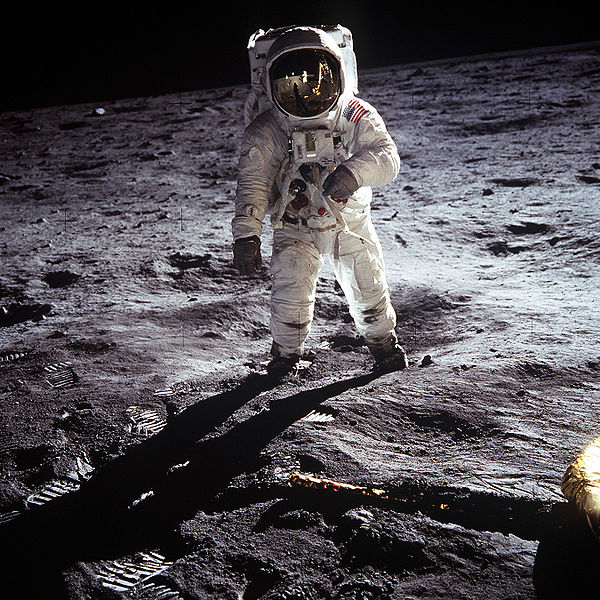

We went to the Moon, and returned, and stopped. There was no moment of disappointment. It just grew over the decades. We were promised the Moon.

What the US didn’t do in space since the end of Apollo:

Put a human on the surface of another planet.

What the US did do in space since the end of Apollo:

Place a variety of advanced telescopes in space

Sent fly-by missions to every planet.

Put orbiters around Earth, the Moon, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

Put landers in or on Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Titan.

Mapped numerous bodies in the Solar System.

(The list continues)

Classical science fiction really believed in space exploration, as humanity’s destiny, as the final frontier we needed to keep ourselves sane, as a way out of the Hobbesian struggle of all versus all. It promised that it would be easy, that it only needed a maverick scientist and his adventorous young nephews to build a rocket in his garage and go to the Moon, that space travel would be an untroubled linear process: from the first satellite to the first men in space to a trip to the Moon followed by a Moonbase, permanent space stations, a Mars colony….

Up until Apollo reality seemed to conform to this fantasy of easy travel to other planets. But then reality set in and all the ambitious plans foresee in the pulps of the forties and fifties and formalised in the classic space books by Willy Ley and von Braun and others were put on hold and then cancelled. For a while there were still the Viking (thirtythree years ago yesterday) and Voyager missions to be excited about, but with the eighties and the disastrous space shuttle programmes and “Star Wars” the dream seemed to die.

Meanwhile, unnoticed by this “old guard” of space enthusiasts, we got a real space research revival in the nineties, one that didn’t fit the neat space race template of the sixties, but which did reveal a Solar system much stranger and more interesting than the boring old “nine planets, a coule more moons and some junk” the old guard grew up with. What’s more, while space colonisation seemed to grow more and more difficult and distant, it turned out you can do a lot of interesting research from right here on Earth, up to and including the discovery of planets around other stars. The Campbellian idea of three men in a scout rocket having to find out if Gliese 581 has habitable planets or not turned out to be unnecessary, which is a pity if you wanted to be a scout, but less so if you’re interested in what the universe looks like.

So now we got a bifurcation in science fiction: on the one hand those who are disappointed that we won’t “Inherit the Stars”, on the other those who argue that “Earth is Room Enough”. And on the gripping hand there are of course those that don’t really care one way or another but just like to read “Of Time and Stars” without having it be anything more than entertainment.