As I warned last month, the municipal garbage collectors in Amsterdam went on strike following Queensday, though waiting until after Memorial and Liberation Day. A week later and the garbage has started to pile up everywhere, both in the streets and at every collection point. This isn’t helped by those assholes who decide to profit from the strike by dumping commercial waste as well. Luckily the weather has been cold enough that stench hasn’t been a problem yet, though with the promise of warmer weather next week and the strike continuing all that rotting garbage may become a health hazard…

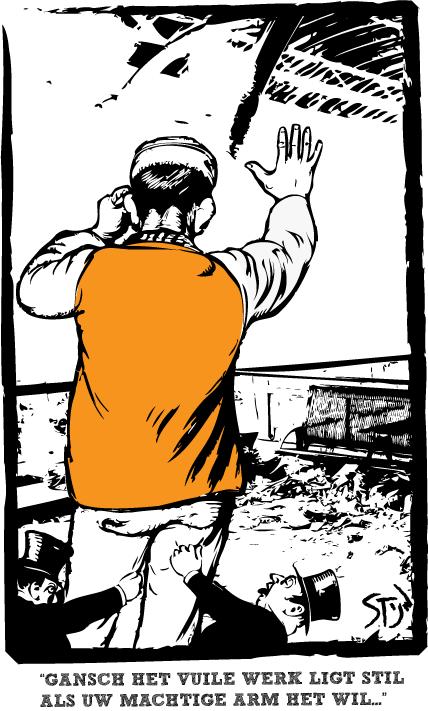

The garbage strike is just one tool the unions are using to try and get the joint municipal employers back to the negotiation table; earlier the parking ticket collectors had a one day strike (very popular) and there have been a few big demos as well. It’s a sign of the growing militancy and changing role of the unions how quickly they’ve used such an aggressive tactic however.

It didn’t used to be this way. For years, if not decades, the unions had become little more than negotiating partners for business and government, operating on a policy of compromise in what has become known as the “poldermodel“, with strikes becoming rare and ritualised pressure tools. It meant a certain amount of social stability, but the price was a growing irrelevancy of the unions to the average worker who did not see the need for union membership anymore, or at best saw it as equivalent to membership in a fitness club. As socialists like Anton Pannekoek warned about more than eighty years ago, unions had become just another tool to manage and control workers.

But in the past decade this has slowly changed. Partially this has been forced upon the unions, as the political climate in the Netherlands changed and became more openly rightwing, but not entirely so. There’s also been an internal radicalisation, a growing willingness to fight rather than compromise, as well as the realisation that the unions needed to change to become relevant again, could not longer permit themselves the luxury of only defending rights already won. One result has been a growing internationalisation of union struggles, for example in the fight to stop the EU-wide liberalisation of sea ports. The other has been a revamp of tactics and methology, heavily influenced by the experiences US unions have had in organising workers in traditionally weak and vulnerable trades, like the hotel cleaners as immortalised in Ken Loach’s Bread and Roses. A lot of these lessons were on display in the earlier cleaners strike I’ve reported on before, were the struggle was organised together with the (non-unionised) cleaners themselves, and instead of impossible mass strikes various companies were surgically targeted.

The current civil servant strike is done in the same spirit, with a series of short, smart actions rather than one long strike. So you had a public rally first, to get people’s blood up, followed by a one day strike by parking ticket collectors to hurt the city councils in their wallets, followed by the garbage strike to make it both public and impossible to ignore. Behind that and less visible in both strikes, as well as elsewhere are less visible and actually quite oldfashioned methods to get workers organised, by union activist actually going to a workplace and talk with workers there, persuade people to become unionised, get a nucleus of such workers to organise the rest of the workforce and if necessary use the same sort of smart, targeted strikes to force concessions from the bosses. And the best thing about this is that finally the unions have stopped doing purely defensive strikes, defending rights already fought for and won decades earlier, but have gone on the offensive, winning rights for those groups of people not having them yet.