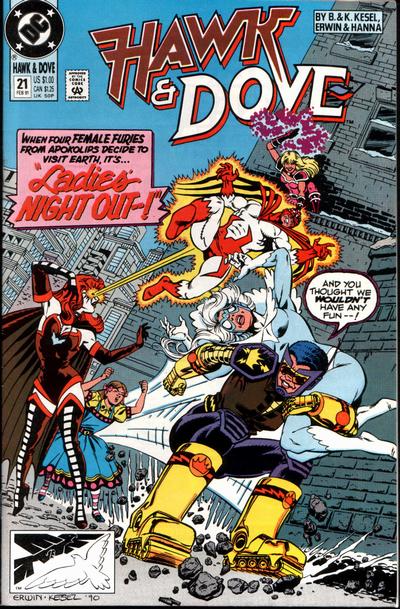

Hawk and Dove have to fight off unwelcome visitors from Apokalips — a group of Femal Furies come to DC hunting for trophies and each trophy means a murder.

The very first issue of Hawk and Dove I bought, way back in 1991. I had real knack for picking winners back then: the series would last for just another seven issues after this. A victim of one of DC more pointless crossover series, Armaggeddon 2001, which ran through all its annuals, where it was an excuse to look into the future. However, the identity of the Big Bad behind it all got spoiled so instead Hawk and Dove got sacrifised to keep the ‘surprise’.

But that was in the future. This issue, like ever, was written by Barbara and Karl Kesel, with art by guest artist Steve Erwin. A done in one story with a couple of new Female Furies causing havoc and our heroic duo barely escaping with their lives. A perfect example of a late Bronze Age comic, with all the ongoing subplots bubbling away in the background.

The entire series was like that. As you may know, Hawk & Dove was originally a Steve Ditko creation, the brothers Hank and Don Hall becoming the living embodiments of arguments about the Vietnam war, with the aggressive, somewhat dickish Hank becoming the Hawk and pacifistic Don becoming the Dove. Having one part of a superhero duo just refusing to use violence makes for an interesting challenge but it never quite worked in practise (and you suspect Ditko wasn’t on Don’s side in the first place, considering.) Some guest appearances here and there, a stint in the Titans and ultimately Don died heroically saving a child during Crisis on Infinite Earts. In 1988 Barbara and Karl Kesel created a new, female Dove (Dawn Granger) and made her and Hawk into representations of Order and Chaos respectivily, as that was a thing with DC Comics in the late eighties. This was done in a five issue miniseries with art by a somewhat obscure artist called Rob Liefeld…

For the ongoing the next year Liefeld was replaced by Greg Guler, who did a great job. The series had a great setting in Washington DC, away from most other superheroes and an excellent supporting cast as well as a good mix of recurring and oneshot villains. Since I got into the series late, most of the earlier issues I got from cheap back issue bins — Tijdschriftenhandel Noord in Rotterdam is where I got most of them. Even though the series ended thanks to a shitty crossover getting spoiled, at least most of the major subplots were wrapped up by the last issue. On the whole, this is the sort of superhero series you don’t see anymore, as self contained as it was, with no pretence to be anything other than a superhero series.