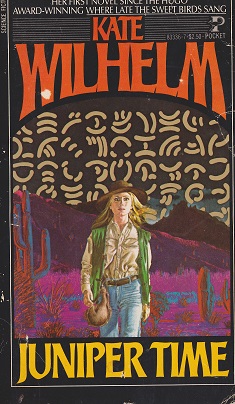

Juniper Time

Kate Wilhelm

296 pages

published in 1979

This got easier to read after the rape, which happened on page 88 but I could see coming from almost the first page. A late seventies science fiction novel, with a female protagonist and a near future setting in which America is suffering a long term hypertrophied economic depression, in a stalemate with the Russians and sliding off to an autocracy (aka standard seventies dystopia #1)? Yeah, there’s going to be a rape. It’s depressingly predictable and while it’s not the worst sort of plot motivating rape I’ve ever read and you could even argue that this time it’s truly essential to the plot, it’s still disappointing to see it used. But once it was out of the way it was much easier to enjoy what is otherwise an extremely interesting novel.

Juniper Time is a novel I first read sometime in the eighties, in Dutch translation, because of the recommendation in an old issue of the Holland SF fanzine. I remember liking it well enough at the time, but also that after I’d discovered cyberpunk, it struck me as the poster child of everything in science fiction the cyberpunks revolted against, as per Bruce Sterling’s introductions to Burning Chrome and Mirror Shades. It’s a political novel, a feminist novel that’s more focused on Earthbound matters than the conquest of space, slow moving and presenting a world that’s Disco Era America writ large, depressed, crime ridden and worn out. I can well understand how dated it superficially must’ve looked after Neuromancer came out. Thirtyfive years on, cyberpunk is just as dated, the glamour has worn off and it’s easier to see Juniper Time‘s strengths.

It’s sometime in the future and America (as well as the world in general, but that is only mentioned, not shown) suffers from a decades long drought and resulting economic depression. As Wilhelm is at pains to point out, this drought is not the result of human activity like global warming, as my first guess would’ve been, but comes from unforeseen interactions of cosmic rays in the atmosphere. Though this is only mentioned late in the book, this is important. Juniper Time‘s America is an inward looking country, struggling to cope with the effects of the drought and depression.

Jean Brighton’s father was an astronaut, one of the people who went to the moon. Arthur Cluny’s father was his best friend; together they were almost singlehandly responsible for getting the international space station started when Jean and Arthur were still children. But while the station got started, the economic depression, the continuing droughts plaguing America meant less and less money could be gotten for it from Congress and their dream died with them. But dreams of space don’t stay dead long in science fiction, not even seventies science fiction, and it’s Arthur who’s pushed by his friends to re-ignite the dreams, his background making him the ideal candidate to make the case again.

That’s all explained in the first chapter, with the next three following Arthur as he gets involved with the effort to get the space station started up again. Arthur here is only a figurehead, important because of who his father and because he can get the papers his father saved when the station was mothballed. But that’s not the only thing that’s taken up his time: he has falled hard for Lina Davies, the most beautiful woman he’s ever seen. His courtship and ultimate marriage to her is not easy to read: Lina remains a cypher, only seen from the outside and only through Arthur’s lust filled eyes, with no hint of personality or intelligence. He’ll end up killing her later in the book.

It’s only in chapter five that Jean returns to the spotlight, working as intern in a linguistic project for a not very considerate professor at the university, trying to prove that thanks to the existence of unconscious grammars, a correctly programmed computer could decode any language without need for a Rosetta stone. Jean also believes in this work, if not to the extend of her employer, but it seems to be her instinctive talents that lead to the breakthrough. Yet because the programme is now successful, it comes to the attention of the military and Jean refuses to have anything to do with them. Which in turn leads to her having to leave, her loss of student status and flat and move into a Newtown filled with refugees and ultimately, her gang rape.

I remember that I had the same struggle reading this novel the first time I read it, back in the eighties. It seems rather perfunctory, with Arthur being an unlikeable dick and Jean the inevitable victim, set in a tediously grim, crapsack world that just seems to slowly grind down. The rape is the ultimate low point in this unpleasantness, distressing to read though Wilhelm is careful not to give too many details and describes it almost clinically. At this point Juniper Time reads no different from many of the rightwing grim ‘n gritty mopefests published in the late seventies. All that changes when Jean goes home to her late grandparents house, in Bend, Oregon.

That’s when Juniper Time comes alive. Unlike the somewhat generic cities Wilhelm has been describing up till now, Bend has the heft and weight of a real place. Abandoned by almost everybody and under control now of the army, it has become a ghost town, a place of safety for Jean. It’s of course a classic response to trauma, a flight back to the safety of her childhood, unspoiled by contemporary reality, no people around to hurt her further. In the newly returned desert she can start to heal

On one of her desert jaunts she runs into an old childhood acquaintance, a Native American friend of her father and grandfather, who finds her after she has collapsed, perhaps settled down to die. He rescues her and through him she finds a renewed purpose in life, as she comes involved with his tribe’s struggle to adjust to the new old world they find themselves in. They’re still trying to find out how to live within the new limits of their homelands, learning what works and what doesn’t and they need Jean both to teach English to those who don’t speak it and establish a dictionary of their language, as support for their new lives.

And here we come to the central message of Juniper Time, embodied in the tribe’s struggle to adjust and relearn the old ways of living in harmony with the land. Usually science fiction is about overpowering your problems, of learning better ways to deal with nature and its challenges, of triumphing over adversary. Here, it’s about adapting to the inevitable. The world is drying up through circumstances humans have no control over. This isn’t climate change as we know it, but a natural, unexplained phenomenon. Save from one suggestion about cosmic rays, we’re never shown what causes the drought, why it continues or why it’s worldwide.

Meanwhile, in the other plot thread, Arthur has gotten his wish, the space station is being rebuild and something …interesting… is found hiding in low Earth orbit, a golden scroll filled with what looks like alien signs. It sends him looking for a linguist, for somebody not beholden to the military or government, to examine the scroll and see whether it is a hoax or not, some trick by the Russians or perhaps America’s own hardliners to put one over the opposition and claim the station for themselves, the key to unlock the status quo.

It of course sends him looking for Jean and he expects to find a victim, somebody shattered by her experiences, but instead he finds a confident, self sufficient woman who helps him for her own reasons, not because he had to manipulate her into it. The contrast between Arthur, who married somebody purely out of lust, then later basically ended up killing her out of spite, arrogant, conceited but convinced he’s a good guy and Jean’s new found quiet strength is strong, must’ve been done deliberately.

Rereading Juniper Time, it does feel as if Jean and Arthur come from different novels, a mashup of the New Wave disaster novel ala Ballard’s The Drought and the late seventies “space will save us from the Carter economic malaise” as written by e.g. Pournelle. I’m wondering whether Kate Wilhelm has deliberately written this as a critique of the latter, of that tendency to think moving into space can solve any problem. Jean’s outlook on life is so much more mature than Arthur’s; she never falls for the alien deux ex-machina but is willing to use it for her own ends.

What with the rape and the general slow burn of the novel’s first third or so, I found this a hard novel to read, but ultimately worthwhile, complex and thought provoking.