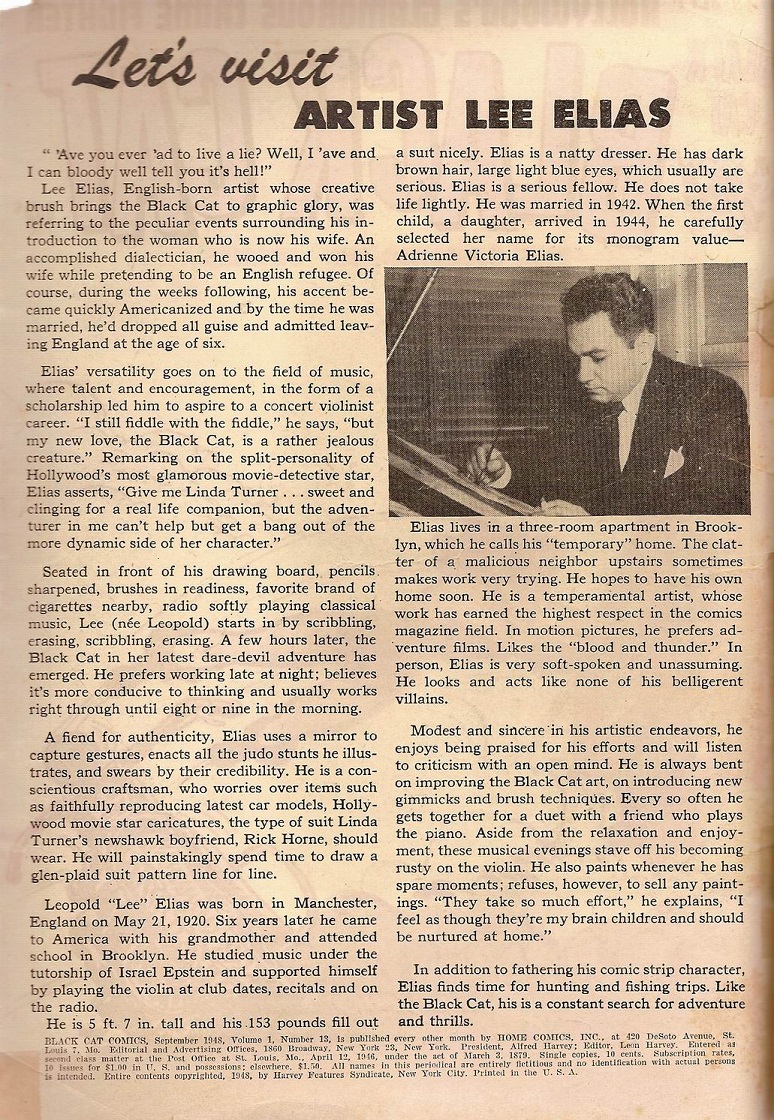

I’m not the only one who fell in love with Eizouken ni wa Te wo Dasu na! when this scene came up in the first episode, right?

There have been several series, most noticeably Shirobako, showing what working on anime is like and plenty more series that just celebrate otakus and fandom, but I can’t recall any other series being this explicitly about the joy of animation. It came at just the right time for me, the enthusiasm and genuine love Eizouken ni wa Te wo Dasu na! has for animation rekindling my own flagging interest in it. And it was this scene in particular which triggered that. It’s that experience of settling down to watch something just to be entertained for a little while and then getting hooked, of discovering a world you did not know existed. The anime Midori watches is a thinly disguised version of Mirai Shounen Conan, a 1978 anime series directed by Miyazaki Hayao. Thanks to his involvement it’s fairly well known, but it’s still a somewhat obscure choice to make as Midori’s gateway anime, a fortytwo year old series. Especially when, as far as I know, this isn’t available for streaming outside of Japan nor is currently in print as a DVD or Bluray.

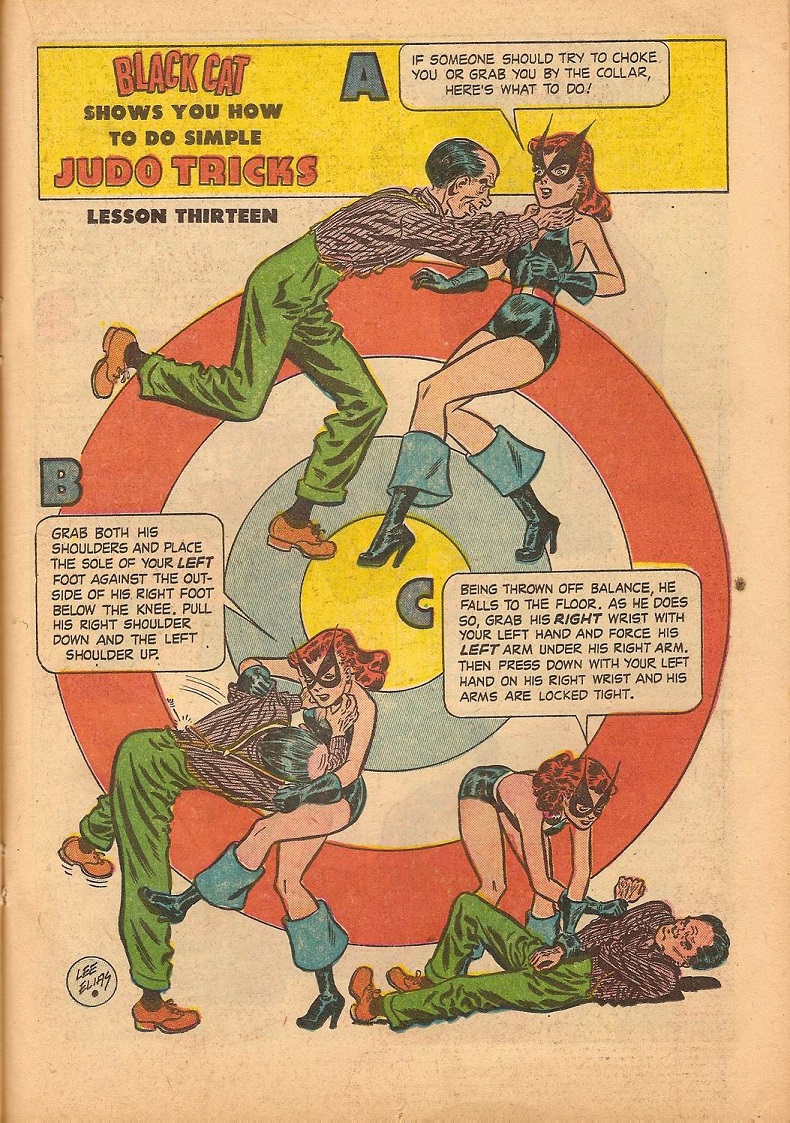

Midori herself explains why this series in particular made her realise anime is something that people actually make, rather than something that just exists. She and her friend are visiting her new high school’s freshmen’s festival and they go to the anime club’s screening of an episode of “Conan of the Lost Island“. Her friend asks her why this is entertaining to her and she responds with the sort of exhaustive detail you should expect from an unfiltered anime nerd. In particular, she explains how an unexplained nonsense idea like an antigravity device powered flying car is made real by how the characters interact with it. How the extraordinary is made plausible by how it affects the characters. How showing a character running with his upper body bend forward against the wind makes him running over the wing of a flying aircraft look real even when you know it’s impossible.

Eizouken‘s high praise of the series made me want to watch Mirai Shounen Conan myself. I finally got around to it late last year, watching it over New Year’s Eve, making it the last anime I started in 2020 and the first I finished in 2021. Even without having been primed for it by Eizouken, I think I would’ve noticed Mirai Shounen Conan‘s physicality. Just take the clip from episode eight above. Conan and Lana have been running from Lana’s abductors, but their boat got hit by a cannon shell and sunk. Conan, still in magnetic cuffs from having been captured before, is stuck to a piece of debris and has to free himself. The way this is shown through Conan’s straining against his cuffs, how you can almost feel the effort he puts into trying to bend the metal he’s stuck to, the liberation once he is free, is rare in anime. Action can feel weightless in modern anime, especially when reliant on CGI. Not so in Conan. This would be impressive in a movie, but in a weekly television anime it’s even more so. The high standard set in the first few episodes is never let up. Nor is this physicality limited to key scenes. Everything is treated with the same care.

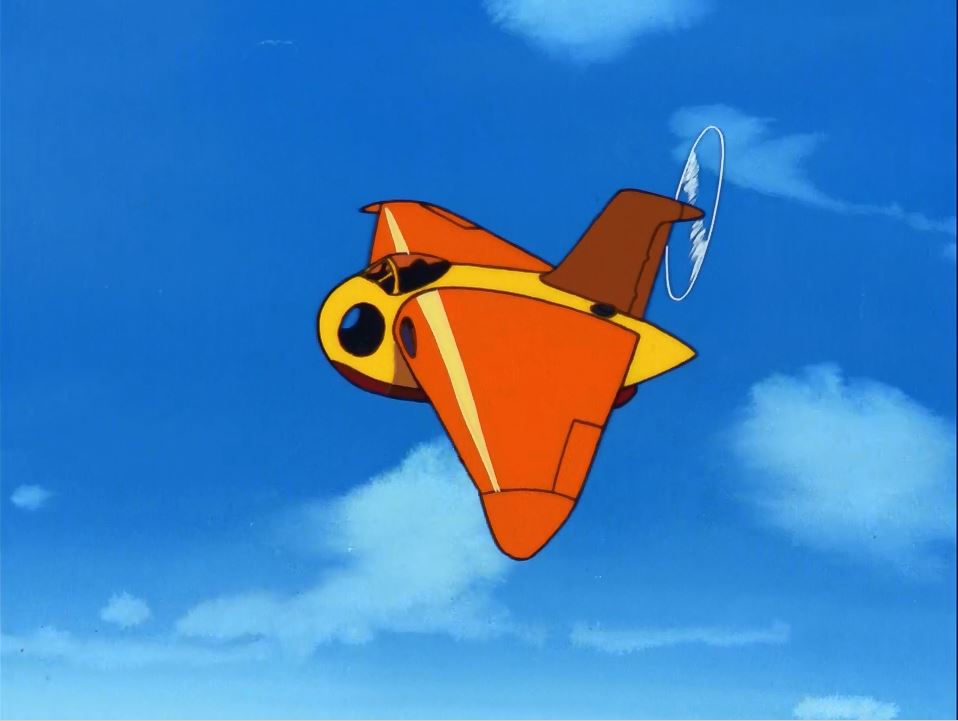

If you didn’t know Miyazaki was involved with Mirai Shounen Conan, it should be clear by the time the Falco, — the airplane above — shows up. It’s such an obvious Miyazaki design and it reminded me of the plane from The Castle of Cagliostro. A pity such a cute plane is being used by the bad guys. The underlying theme of the series may be about how science unleashed in service of greed is bad and humanity needs to return to a managable technology level, but Miyazaki still makes that technology look hella seductive. Even the world destroying monster planes featured in the narration that starts each episode look cool. That conflict between morality and aesthetic we see a lot in Miyazaki’s later works, but Mirai Shounen Conan was the first time it was displayed like this. Miyazaki can’t help but display the glamour of the very technology that his stories want to condemn. The weapon destroying the world being monstrous airplanes rather than more mundane nuclear missiles is telling in itself. A romantic touch even in armageddon.

Miyazaki’s essential humanity is also on display here: as with Terry Pratchett, few of his villains are completely unredeemable. Throughout the series there are hints given as how the sheer desparate struggle for survival made Industria into the horrible dictatorship that it is when Conan is taken there. It’s clear that in a system where people are reduced to solely how useful they are to the survival of Industria, the competition for safety, the desperation to not slide down into the unwanted masses, people become villains. As a contrast there’s High Harbour, which like Industria found itself having to rebuild civilisation from scratch, but without even the advantage of a fully functioning nuclear reactor at their disposal. High Harbour had no choice but to settle for roughly a 19th century level of technology and build a society you could live in comfortably. Industria, for all its technical prowess was still operating on “lifeboat rules”. At best it’s a system that breeds opportunists like captain Dyce, eager to do whatever it takes to earn a safe spot within it, but ready to sell it out the moment it becomes advantageous to do so.At worst, you get would-be tyrants like Lepka, eager to re-use the same weapons that destroyed the world to make himself its master. The only person with any true loyalty to Industria is Monsley, the captain of the Falco, who as a young girl saw her parents die in the apocalypse right before her eyes, she herself only saved by her dog having run away. The crimes she commits are not done out of self interest, but purely for the survival of Industria and its people. Both Monsley and Dyce are not irredeemable villains, just people driven by their terrible situation to do what’s necessary to survive.

Another way you can tell this is a Miyazaki production is through the character acting. The physicality that is key to making the fantastic believeable in his work, is also used to show the emotions and character of his personages. The first time I saw Conan running I knew this was a Miyazaki series; by the time I saw the sequence above, in episode three I was certain. The sheer physical joy in the animation is a dead giveaway. Here too physical impossibilities like Conan and Jimsy almost running vertically up that cliff side are sold both by the sheer confidence of the animation and the fact that they struggle to both fit through a bifurcated tree trunk seconds later. Each of them straining to out run the other, as shown through how thye throw their bodies foreward, stretching to gain even a centimetre of advantage. Then later, as they lose control running down hill, how it’s shown through them leaning back, attempting to break their speed without losing ground. While the movement and speed are exaggerated, the way it’s shown is firmly anchored in real life experience. You see kids running like this. Little dialogue is needed to show the stubbornness and competitiveness of Conan and especially Jimsy here.

What Mirai Shounen Conan offers is the unpolished version of what Miyazaki would perfect at Studio Ghibli. It’s a study in what you can achieve even with the limitations and the budget of a television anime. If you love animation for its own sake you need to watch this. Getting a great story and likeable characters as well is a bonus.