For those looking for an artist to scratch their Hugo Pratt itch, may I recommend Attilio Micheluzzi?

From the first page of Mombassa Road (1989) Micheluzzi’s qualities are obvious. Like Pratt, he owns a debt to Milton Caniff and the great American adventure strip tradition and even in this early work it’s clear he’s a master of his art. To be honest, when I picked this up last year at the Haarlem stripdagen it was only because it was only a Euro and the cover looked interesting. Micheluzzi is an artist I knew little about otherwise, just one of those vaguely familiar names that popped up in comics zines and the like back in the eighties but I never paid attention to as I was into superheroes at the time. Having broadened my tastes in the decades since, I end up buying books like this just on the off chance, if they’re cheap enough. Didn’t read it though, until last Saturday.

Micheluzzi it turns out was a contemporary of Pratt, born in 1930, three years after Pratt and died in 1990, five years before him. He started his career much later than him though, when he was already in his forties, in the early seventies. From what I’ve found of his he specialised in the same sort of historical adventure stories as Pratt, working for the sort of Italian comics magazines that were a bit more quality than the blood ‘n tits fumetti series. Both working solo and with scenarists, he created several such series for various magazines, as well as several stand alone, longer stories about actual historical incidents, like L’uomo del Tanganyka, about the German struggle in South-West Africa during WWI.

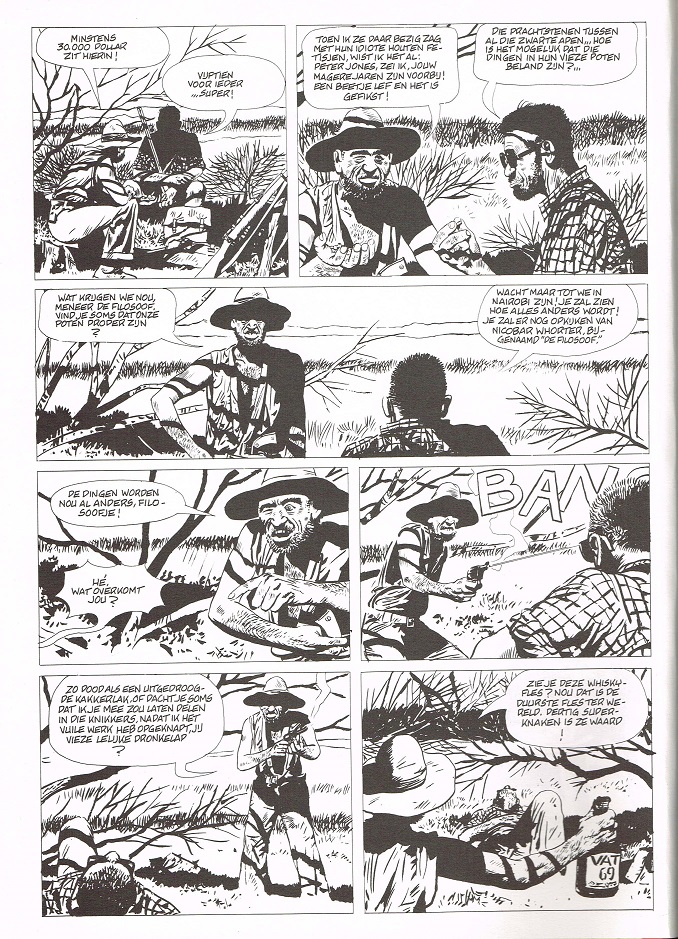

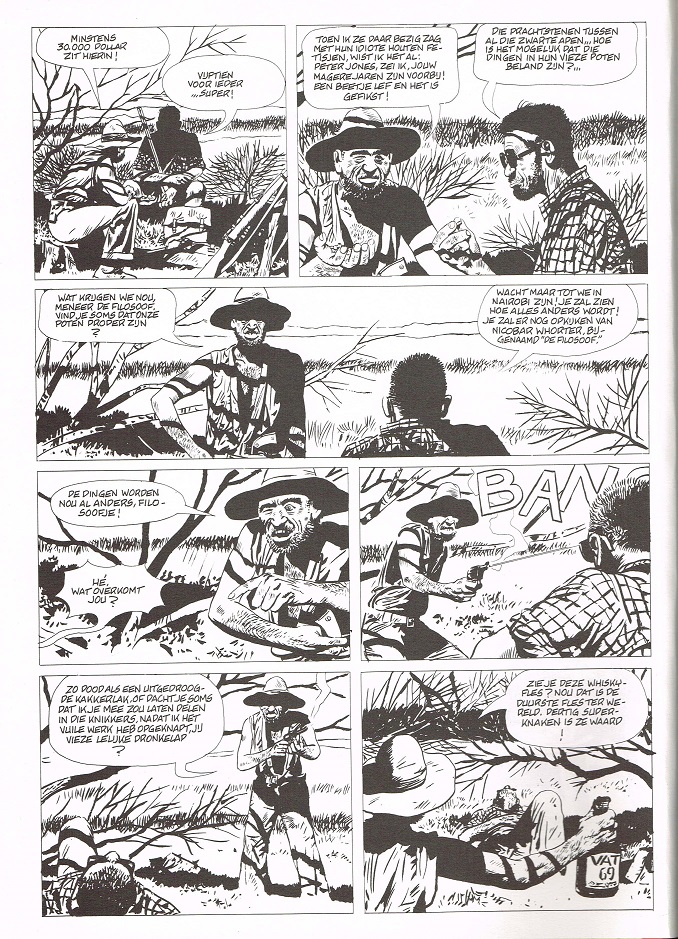

Mombassa Road is a Dutch translation of three of Micheluzzi’s earliest stories, Starring Johnny Focus, whom he created in 1974. Focus is a photo reporter in post-war but still colonial Kenya. Square jawed, blonde and unshaven he’s your typical hero moving through typical pulp plots. In the first story of the three he gets caught up with a pair of thieves who stole diamonds from a local Masai tribe. One of them shoots the other but fails to kill him, while he himself ends up in quicksand, which is where Focus finds him. The rest of the story is a game of cat and mouse between the surviving thief and Focus, until the Masai come to get their diamonds back. The remaining two stories pitch Focus against an ivor smuggling ring, while he also has to rescue a young woman from being devoured by a crocodil. She immediately falls in love, he’s not interested.

Even for 1974 this is old fashioned stuff. All the main characters are white, with the few actual Kenyans that we do encounter there as either victims for the villains or as deo ex machina as in the end of that first story. If not for the helicopter featured in the second story this could’ve just as well taken place in the thirties. You wonder why the Dutch publisher chose this series and these stories from it to feature in this collection. Especially because they’re from the middle of the original series and the last story ends with the ivory gang still on the loose. Micheluzzi had been published in Dutch before, e.g. the aforementioned L’uomo del Tanganyka, but these had been part of a broader reprint of the original Italian series L’uomo del Tanganyka had been a part of. This however was a deluxe standalone volume with no real editorial justification offered of why they choose these particular stories. As far as I’m aware this was the first and last time any of the Johnny Focus stories were translated into Dutch. The same publisher would instead start reprinting Micheluzzi’s Ross Benton series instead, not long after this was published.

Was there enough name recognition for Micheluzzi at the time that this made sense? Or did they bank on his art’s resemblence to that of Hugo Pratt, who they had published in the same Création series previously? As this was never covered in Stripschrift or any other Dutch fanzine as far as I can tell, I’ve got no idea even of how it was received. It can be very frustrating as a Dutch comics fan to retrace the history of why and how something got published.